The development of wireless technology has grown apace in the last few years, creating a seemingly limitless number of applications across a wide array of sectors. The snazzy new catchphrase that encapsulates this market is The Internet of Things (IoT).

Essentially it has been estimated that by 2020 there will be 26 billion connected electronic items, including wearable devices, mobile telephones and a range of domestic appliances from smart TVs and refrigerators to radiator thermostats and security systems. The crucial question remains: who is liable when things go wrong?

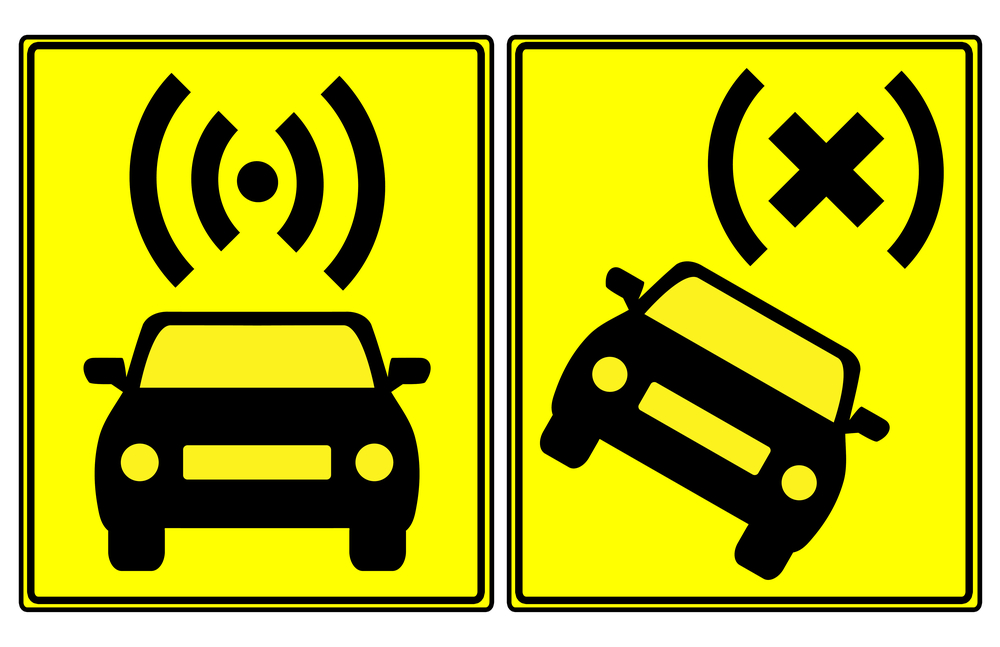

The most topical example of the moment is that of the driverless car. Cars are currently being tested in the US and the UK, and it is not unimaginable that we will see fully autonomous vehicles on the roads within the next few years.

The theory is that the level of cutting-edge technology employed in driverless cars virtually eliminates the possibility of a collision, but inevitably something will go wrong, in which event where does liability lie? Is it with the operator/occupant of the vehicle or the manufacturer?

>See also: Surfing the choppy legal waves of Internet of Things: what your business needs to know

There are a number of parties who might share liability, including the vehicle’s owner, the operator, the manufacturer, the suppliers/importer, the service provider and the company who supplies the data instructions to the car’s computer. Each party may be found to face civil (and in some cases criminal) liability to a greater or lesser extent.

In the event of a collision, the first question will become not “who” but “which vehicle” was at fault and why? If parties are unable to resolve where liability lies, it will be determined by the courts.

The available evidence would be examined in detail and a judge would assess whether each party is liable in law and the extent to which their fault had contributed to the loss.

Currently, over 90% of collisions are found to involve human error, but vehicle manufacturers may be held liable where it can be shown that they failed to fulfil their legal obligations. In a future failure of an automated vehicle, it is very likely that the manufacturer will be found at fault.

Wearing your tech on your sleeve

IoT is also making a huge impact in the healthcare sector. Labelled the ‘Internet of Living Things’, this area focuses on delivering health data from wearable or implantable devices that monitor a range of metrics that may be processed through mobile device apps and transmitted to healthcare professionals.

This technology has a myriad of applications but its primary use is to monitor chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. This information is passed digitally to the treating physician.

Furthermore, many sensors and wearables have been developed to detect accidents, fits, seizures or heart attacks and then alert the emergency services. Sensor technology can also be employed in conjunction with virtual reality environments, which is useful in the provision of remote rehabilitation and physiotherapy for patients recovering from injury.

According to a report published by the IHS, the global market for wearable technology will rise to 210 million unit shipments and will generate $30 billion in revenues by 2018. It also estimates that by 2017 some 18.2 million health and wellness systems will be shipped worldwide, with global revenues for this market expected to reach $16.3bn.

However, this is a field that needs to be approached with caution. Providers of healthcare technology have already seen the recall of apps that have been calibrated incorrectly and failed to correctly monitor medical conditions.

This could lead to claims against those who make such products (and their suppliers). Whilst patients may benefit from reduced healthcare premiums in exchange for supplying their personal data, it is unavoidable that concerns are raised over the issue of cyber security.

Watch out, cyber’s about

The exponential increase in the collection of data and the uses to which it is put creates a host of data protection issues. The data collected by automated vehicles and through ‘black boxes’ would provide detailed information about a person’s whereabouts, as well as potentially providing information about their compliance with the law (in the form of, for example, speed limits).

In healthcare, wearable and implantable devices will potentially be able to collate detailed information about a person’s health. Any system that enables payments to be made may contain information about bank accounts or credit card details. All of this information may be of interest to commercial organisations and criminals, and its loss could cause enormous distress to individuals.

There have been recent reports of hackers being able to access car systems enabling them to interfere with power steering, GPS, speedometers and odometers (although such weaknesses in car systems have been known since at least 2010). As one analyst said recently, “The less the driver is involved the more potential for failure when bad people are tampering with it.”

Similar concerns exist in relation to medical devices, where the possibility of a hacker interfering with the device (such as for monitoring or injecting insulin) have been raised.

>See also: Are we ready for driverless cars?

Researchers in New York have recently suggested that there is a high risk of cyber-attack against those using artificial pancreases. As with anything else in the IoT, if information is not encrypted then there is a risk that hackers will be able to intercept data and send false information or instructions.

Failing to hold or process this information securely could lead to a breach of data protection legislation or an infringement of privacy rights and claims for compensation. Failing to build in adequate security could also lead to claims.

Household Liability

No matter what the device or its usage, there is always the potential for it to fail and cause damage to property. Where does the liability lie in the case of a defective smart boiler thermostat or timer that fails to respond correctly to instructions causing a fire or flood?

Claims arising from such incidents may target manufacturers, own-branders, service companies, designers, retailers and importers, all potentially calling upon different insurance policies.

While insurers may limit their cyber exposure in general liability policies, liability arising as the result of a defect or fitness-for-purpose issue may trigger cover.

Establishing how and why a software or component fault occurred poses fresh challenges. As with most product liability disputes, the outcome may hinge upon the credibility and industry knowledge of the experts involved.

Expert disciplines are developing fast to match the need to gather and analyse forensic evidence in indemnity and liability investigations.

Sourced from Jim Sherwood and Tim Smith, BLM