It is widely recognised that when companies have to cut costs, training is almost always one of the first things to be affected. And that was certainly the case at British Airways. When the airline embarked on a round of cost-cutting measures in 2000,

|

||

the brief given to Alison Walker, training and development manager, was to cut all classroom-based training unless it was mission-critical.

In response, Walker gathered together a number of BA’s training departments to examine the possibility of delivering training online in subjects that were not central to the airline’s activities – such as IT training and various management training courses, including conducting performance reviews. Walker now estimates that, over the three-year period since BA began its e-learning initiative, it has saved around £8 million – chiefly because it spends so much less on hiring classrooms, staff travel and accommodation.

Computer-based training (CBT) has been around for more than a decade – employees have long been able to access training programmes via floppy disk or CD-ROM. But CBT frequently proved difficult to monitor and many organisations failed to reap the promised cost-savings. CD-ROMs, for example, would repeatedly go missing, while unsophisticated tracking mechanisms – often purely in the form of an Excel spreadsheet – meant that some employees would be passed over for training on important, compliance-related issues, or simply would didn’t bother to do it.

When e-learning first came to prominence at the height of the dot-com era in the late 1990s, it was hailed as the panacea of skills development. Because web-based training was so quick and cost-effective to distribute compared with the cost of gathering employees in a classroom, and could be electronically tracked, many organisations rushed to put training content online. John Chambers, CEO of networking giant Cisco even went as far as to call e-learning “the next killer app”.

But as with many so-called ‘killer apps’ that emerged from that era, e-learning never really took off. “Businesses became so obsessed with the cost-cutting hype surrounding e-learning that they believed they had to build their own content, so many of them just took a load of PowerPoint presentations and put them online,” explains Devrim Celal, head of learning services at IT consultancy Sapient. Others invested heavily in off-the-shelf content from the swarm of e-learning companies that had sprung up in the hope of a quick revenue opportunity, only to find that it wasn’t compatible with existing systems, or that much of it remained unused. Consequently, estimates Celal, most e-learning projects are still only around 15% complete.

Rethink

The irony of e-learning, is while it offers clear cost-cutting potential, organisations that focus solely on costs are most likely to get it wrong. “Don’t get too hung up on the cost savings e-learning can provide,” warns Martin Sloman, an advisor for the UK’s Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. “Eighteen months ago we regularly received phone calls from members asking how they could cut training costs through e-learning. The answer was not always welcome: ‘If you start from that premise, you will fail’.”

Research from US-based return on investment (ROI) consultancy Nucleus Research supports this view – while some of the companies it looked at in a recent ROI study on e-learning generated returns in excess of 1000%, it was those companies that made an ongoing investment in the development and management of training content that achieved the best results in the long term.

Combined with classroom-based training and with the appropriate level of management, e-learning, promise analysts, can deliver significant savings or help to create efficiencies where they are needed. The National Health Service (NHS), for example, uses e-learning to relieve some of the burden from overworked doctors and nurses. Nurses can learn basic medical

|

||

procedures using the web in the staff room while they are on call, while administrative staff can also develop skills that can take some of the form-filling tasks away from nurses so they can focus on patient care.

E-learning can also increase organisations’ time to market. Chip manufacturer Intel, for example, uses web-based programmes to teach its sales staff about new products, and has also used e-learning to train up new IT staff. Martin Curley, director of IT innovation at Intel, says that using online material for IT training has cut down six months of classroom-based training into 16 online modules of 10 minutes each. This project alone has saved Intel $250,000.

Adoption battle

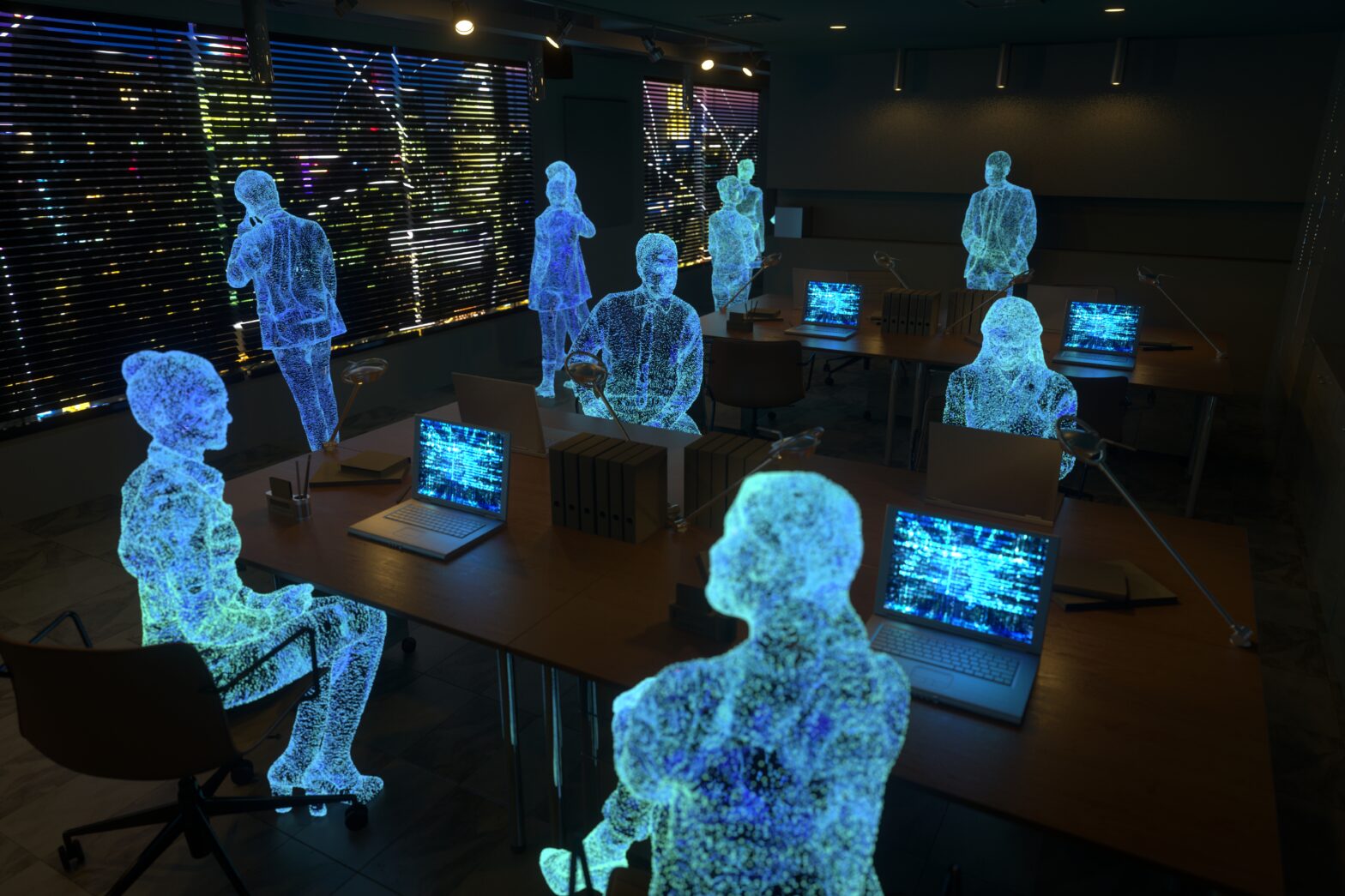

Among the early adopters of e-learning tools, the greatest challenge has been encouraging user acceptance. Many employees enjoy the social or networking aspects of classroom-based training courses, for example, and may feel their right to these privileges is being taken away if that course is transferred to the web.

“E-learning is like any piece of software,” says Karen Murphy, who manages e-learning programmes at pharmaceuticals company Bayer in the UK. “If you don’t use it on a daily basis users opt out.”

Bayer found that one of the easiest ways to encourage users to adopt the system was to provide some form of compulsory training online – for example fire and safety training – so that employees could get used to online training and be more receptive to other online courses. BA’s experience was similar. “The killer app was a fire training course,” says Alison Walker. “It had to be done online, but once users were in the ‘learning zone’ they could then see what else was in our online training portfolio.”

Another important factor in encouraging user adoption is ensuring the content is both appropriate, and where possible, interactive. Martin Curley of Intel cites research by the University of Delaware that concluded that people are 80% more likely to remember what they see, hear and do simultaneously than what they read as a piece of text. With this in mind, Intel has built a peer-to-peer knowledge network that enables employees to download rich media files and interact with them without compromising Intel’s bandwidth requirements.

The majority of organisations, however, have to settle for simple, off-the-shelf content from e-learning content providers such as NetG or Global Knowledge. These companies have vast libraries of pre-packaged, web-based content covering anything from IT training to ‘softer’ skills such as performance management or communications skills. But while these work well for generic skills that are part of every organisation, they don’t always fit every business, says Will Newby, group training and competency officer at Britannia Building Society, which introduced an e-learning programme in December 2002 to inform employees how to deal with potential cases of money laundering. “There’s lots of ‘best practice’ out there, but it’s only really suitable for Best Practice PLC. We needed something highly bespoke.”

It is issues such as these that have led to the failure of many e-learning projects, believes Robert Chapman of classroom-based training provider The Training Camp. “The efficiency arguments for e-learning miss the point,” rues Chapman. “Maybe it costs less and it’s more efficient, but it’s how quickly employees can absorb and implement skills in the workplace that saves the company money.”

This is why the organisations that have met with the greatest success in e-learning projects have blended online training with as many other appropriate forms of training that are necessary. At BA for example, managers on a performance management course do two of the three required modules online, but the third and most important – the practical application of that knowledge – is done in a classroom.

The same worked for UK utility Scottish Power, which has reduced the time field service engineers spend on classroom-based training from three days to two – much of the theory can be delivered online, but those two days of practical training in the classroom still need to be done. “The most effective way to use e-learning is for knowledge transfer rather than actual skills development,” concludes McElvie. “You can’t change someone’s behaviour with online learning, but you can give them the knowledge that can help change their behaviour, and apply those practical skills.” And if substantial savings can be made in the process, so much the better.