They don’t call it the ‘CrackBerry’ for nothing. Over the past two years, Research in Motion’s mobile email device, the BlackBerry, has become the must-have pocket accessory for senior executives everywhere. In the last three months alone, over a third of a million new users have got hooked. But the wildly popular handheld computer has a dark side – and those in IT operations know all about it.

Plainly put, email as a mobile application is being granted a status far in excess of its value to the business. And its impact in terms of support overhead – not to mention the degree to which it exposes the reliability of IT services – can be career-threatening.

Work-life balance

Ever since the BlackBerry gained acceptance within the enterprise, stories about its addictive properties have circulated. A survey of BlackBerry users at consulting firm Atos Origin asked whether the introduction of the devices had improved users’ work-life balance. The results were either neutral or negative, reports Jennifer Kwok, principal consultant at Atos UK: “There was a feeling from many users that because they could connect, they had to. When an email arrived, it had to be read.”

But ‘CrackBerry’ addiction soon wears off, says Forrester analyst Brownlee Thomas. “It tends to happen when it’s seen as a status thing, so for the first nine months you have to check it all the time. After that, people get used to it beeping, and learn to ignore it if they’re at home.” While some users struggle to find a comfortable level of usage for the device, IT managers can be placed in a far more tortuous position. One IT director, at a UK-based credit card company, explains: “My BlackBerry has meant that I’ve become the help desk for the rest of the management team. Rather than call support, it’s easier to email me.” Another CIO handed back his BlackBerry after he found his sleep patterns being interrupted by his globetrotting CEO.

Usage policies may help find an acceptable level of intrusion from BlackBerrys, says Kwok. Many organisations have rules governing how IT equipment should be used, but fall short of telling users when a mobile device may be switched off.

That view may not be shared by device suppliers, who insist email is mission-critical. But within the IT organisation there is a growing realisation that mobile email may be as much a curse as a blessing.

At the very least, the device’s popularity among senior management teams can overshadow other achievements by the IT department. As David Weymouth, CIO at banking giant Barclays, says, perceptions can get a bit distorted. In 2004, when senior management was asked to identify the IT function’s main benefits, they did not mention the $1 billion in cost savings that IT had delivered over three and a half years, nor the fact that IT spend as a percentage of revenue was down while user satisfaction had moved up 25 percentage points. The main benefit for them was that Weymouth had provided them with BlackBerrys, he recounts with a sardonic smile.

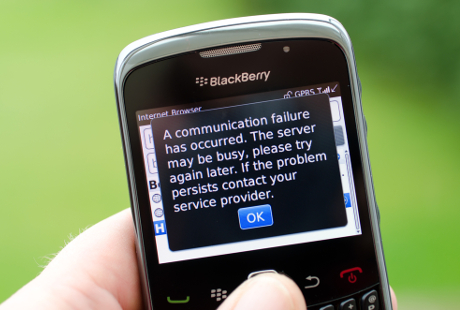

Even more detrimental to the IT organisation are the BlackBerry’s unforeseen side effects, placing disproportionate burdens on already busy staff. One major problem reported is the emphasis BlackBerry places on email systems. In the eyes of many users, remote email has become the business’s most important application. They suggest that it should be better supported, more reliable than any other application. And that shows when it goes down.

The upper echelons of the company now have direct visibility into the status of their email systems. They may not know if there was a three hour outage with sales order processing, but when their BlackBerry goes quiet, they are on the phone screaming – at all times of the day and night.

The email plague

In some senses the popularity of the BlackBerry is paradoxical: It has clearly become an indispensable device for many executives, and yet in most cases it only provides access to what is arguably a noncritical application, namely email. And even though the most recent BlackBerrys are actually capable of supporting many other applications, the perception is that it is the right technology at the right time. It is so successful because “we’ve been waiting for a device like this forever,” says Brownlee Thomas, principal analyst at Forrester Research. It is a relatively cheap way to keep in touch with the office and it allows for more detailed communications than simple text messaging, she points out.

And while such pent-up demand for an easy-to-use, content-rich messaging system led to an explosion in demand during 2004, momentum is still building. While it took RIM five years to ship its first million units, a mere 10 months later, a second million have been sold. Forrester predicts that sales will hit three million shipments annually by 2006.

RIM certainly feels it has come up with the iPod for the executive class. The big advantage of the BlackBerry, says Rick Costanzo, commercial operations manager at RIM Europe, is its ‘push’ capability. This ensures that arriving email is sent directly to the device, rather than having to synchronise in the office, giving mobile workers a sense of being connected to their headquarters. “Of course this means that users know in real time if email isn’t working,” he says. “But we’ve found that it’s given companies a chance to explore the dynamics of their email systems and make sure they are robust.”

BlackBerry’s popularity has seen a proliferation of mobile email devices from other vendors greedily eyeing RIM’s success. So while RIM has been busy sorting out the legal niceties of exactly what patents it owns (see Financial report), vendors like Smartner, Good Technology and Visto have developed rival ‘push’ messaging capabilities.

Even if a more competitive marketplace drives down prices, one crumb of comfort for under-siege IT management is that the upfront and support costs may still curb further mobile email deployments beyond the executive class, in spite of wider demand.

A growing army of mobile email users has serious consequences for the financial health of the organisation, says Jack Gold, vice president of Web &Collaboration Strategies at analysts the Meta Group: “Few organisations understand what wireless email deployment costs them, and even fewer understand the implications for userselection criteria or return on investment.”

Naturally, RIM is keen to downplay the costs of deploying its platform. “We’ve made it as simple as possible: the Enterprise Server can be put on a low-end box and managed by someone with a [Microsoft] Exchange background,” says Constanzo. Added to that, its own research suggests that BlackBerrys allow users to reclaim almost an hour of ‘deadtime’ a day.

Such is the demand for BlackBerrys that organisations that try to limit deployments are faced with devices arriving through the ‘front door’. “We’re getting requests from staff, some of them quite senior, who’ve been out and bought BlackBerrys and want them supported,” says Ian Croxford, head of IT systems services at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. “We have to explain that we looked at the costs of supporting them, and decided on a very limited rollout. They don’t tend to like that answer.”

The strategy of limiting support for mobile email devices is the only cost effective way to manage a deployment, says Gold: “Organisations must carefully control costs and evaluate who should be enabled with wireless email.” This can be a popular approach with FDs but a source of hostility from those denied a BlackBerry.

The critical application?

One of the main charges levelled against the BlackBerry is that it places undue emphasis on supporting email systems. RIM’s Costanzo rejects this argument: “If you’re involved in bringing in new orders, for example, immediate access to email is mission-critical.”

Email also plays a vital role in users’ perception of the IT function, says Neil Dagger, a business manager at Hewlett- Packard UK. “It’s about transparency. If you can show the users in the field that you can provide email to them, they’ll have a better appreciation of the service you’re delivering.” The sales teams whose commission increases by closing deals on the road can even become advocates for the IT department.

While there may be advantages for certain categories of staff, it does not follow that remote email is a vital application for all. Nonetheless, the sense that people need to be connected to the office at all times has both driven the demand for BlackBerrys and intensified the pressure on IT directors to support them 24×7. “It has created a massive expectation that having a BlackBerry is like having an office in your pocket,” says the V&A’s Croxford. “It isn’t realistic. There’s very little understanding from the users about the limitations of these devices.”

Consequently, even when the service goes down because the telecoms network is unavailable, it is the IT department that is the first point of contact (and the target of blame) for users cut off from the regular supply of emails. Moreover, the profile of the BlackBerry users – CEOs, FDs, sales directors and so on – means that keeping email systems up and running has acquired a higher priority than it otherwise might have.

As the IT director of a UK-based financial services company explains: “My CEO sees his BlackBerry as a live evaluate of how well the IT department is performing. If email isn’t up and running he wants to know what he’s been spending all this money on IT for.”

Another London-based IT executive describes a potentially career-damaging scenario: his CEO was in New York closing an important deal when his BlackBerry went dead for several hours; the system also lost access to all email from the last month.

With that in mind, many IT managers are allocating a disproportionate amount of IT resources to supporting remote email. But the popularity of the devices with users, and to a lesser extent, the social kudos of having one, means that the phenomenon is here to stay. Meta predicts that 50% of organisations will have implemented wireless email within two to three years, and 75% by 2009.

The only way to manage this growing influx of mobile email is to establish controls over who qualifies for a device, and to base that decision on the value that the business will get in return, says Meta’s Gold. “Organisations must evaluate return on investment versus total cost of ownership to determine who in the organisation should receive [these devices],” he advises.

The warning to senior IT staff: set economic groundrules covering the issuing of BlackBerrys and other mobile email devices. Otherwise the first killer app to be embraced by senior management since the spreadsheet may come to haunt IT.

Blackberrys in the enterprise: Atos Origin

For companies such as Atos Origin, the ability to get email while working away from the office can be a real boon. Because its consultants spend such a large proportion of their time working at customer sites, the IT services company wanted a simple method of keeping in touch. “Previously we had no quick way to access email remotely,” says Jennifer Kwok, principal consultant at Atos UK. “Carrying a laptop is not always practical, so BlackBerrys looked like a good option.”

The popularity of BlackBerrys also presented Atos with an opportunity to deliver consultancy services for its own clients; its own trial would give it firsthand experience in ironing out problems.

And like many organisations that have opted to roll out BlackBerrys, Atos soon found itself inundated with requests for the devices – partly due to status. Atos developed a matrix, matching requirements such as the need to access email and business applications and to download files against the range of devices available. “For a number of those that got BlackBerrys, we chose models capable of handling calls, and replaced their mobiles,” says Kwok.

While most users reported productivity gains, there can be extra costs. Like many organisations that have undergone mergers and acquisitions, Atos does not have a single IT infrastructure – therefore implementing the BlackBerrys meant duplicate mail servers, VPNs and helpdesks. “Support costs can be substantial for more complex organisations,” says Kwok. “In the end, you can’t give everybody the mobile device they want.”