Emboldened and supremely ambitious, the ever-formidable Chinese economy undoubtedly presents an exciting emerging prospect in the flattened landscape of globalised commerce. But the proposition is not without significant caveats. Indeed, had

Perhaps the most compelling evidence yet to surface emerged at the tail end of November 2007, when anti-virus giant and data security specialist McAfee issued its closely read annual Virtual Criminology Report. Drawing on expertise from the Serious and Organised Crime Agency, the FBI and even NATO, the report outlined the growing threat of web-based global corporate espionage, describing a “new cyber cold war” with “

Two days later – as if on queue – Jonathan Evans, director general of

None of which is to say, however, that

But

The opening salvo

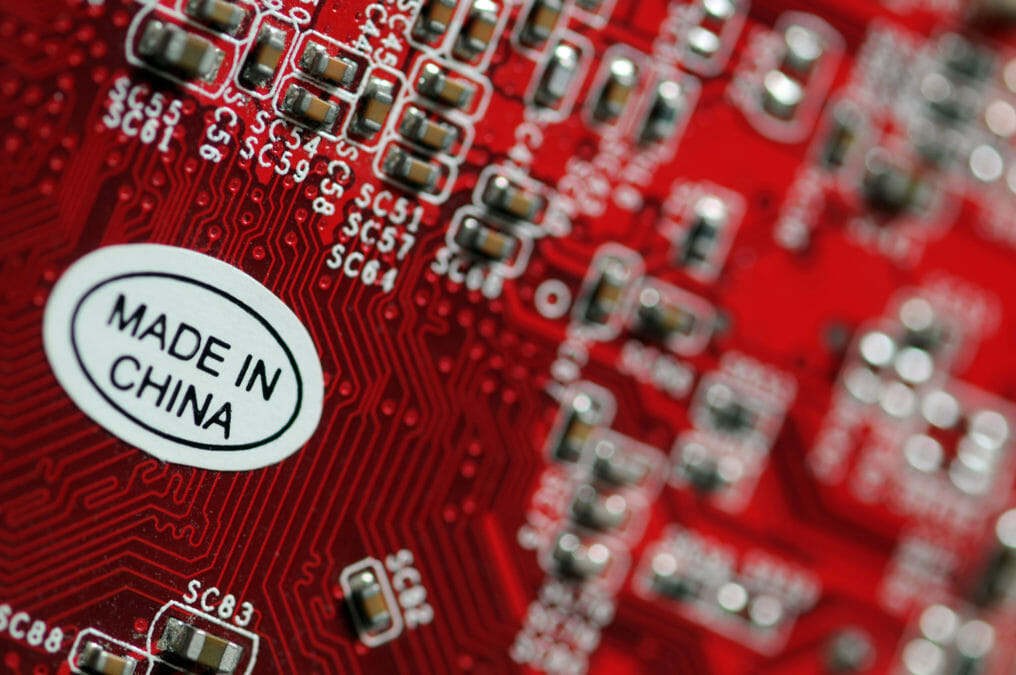

The country has made no secret of its desire to become the world’s predominant cyber power. This was starkly underlined in September 2007, when The Times – having gained access to a Pentagon report – revealed that two hackers working for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had drawn up a so-called ‘blueprint for cyber war’, in which the electronic crippling of key financial, military and communications networks would serve as the opening salvo to an out-and-out physical conflict.

In such plans, the Pentagon alluded, was clear evidence of

Far reaching as it might sound, the plan is not purely aspirational. According to Paul Sop, CTO of Prolexic, a DDoS-mitigation company that blocks web-based attacks on a daily basis,

In both cases the attacks were designed to steal information, and in both cases the finger of blamed was pointed at Chinese-based operators – potentially directed or sponsored by the Chinese state government. Closer to home,

Scale and scaleability

Few will be surprised to learn that, in every instance, the Chinese government firmly denies any allegation of involvement. Proving conclusively otherwise, however, is extremely difficult. First, IP addresses are easily spoofed, meaning that the source from which attacks appear to be emanating may prove false. Secondly, the sophistication of criminal distribution networks, in particular the rise of botnets, also obscures the real actors. Take for example malicious email traffic: according to Secure Computing, a global security appliance provider, Chinese machines are responsible for 9% of all malicious email traffic in the Asian region – a figure that Phyllis Schneck, chair of InfraGard, the FBI-run IT security programme, and vice president of research Integration at Secure Computing, regards as “pretty significant”.

However, she continues, this is not the smoking gun. “All we see is IP addresses sending traffic. It’s therefore hard to know how many people of a certain country are involved. It could be a group based in the

Evidence provided by information security specialists seems to confirm this. According to Kaspersky Lab, for example, up to 40% of global malware on average emanates from

Malicious intent

Nevertheless, many security experts believe that scale is not the only way in which

Simon Owen, head of EMEA security at consultancy Deloitte, does not believe this behaviour is consistent with traditional online criminal activity, the pursuit of which is immediate financial gain. In such instances, information theft largely relates to bank account details, online banking login details and personal identity details, all of which are harvested to perpetrate financial fraud – either directly or through identity theft. This activity is usually targeted at consumer-facing websites. Rather, says Owen, who was briefed by the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI) regarding the CIA’s December warning, the information stolen in attacks publicly blamed on

Furthermore, the complexity and intelligence of the attacks has advanced so greatly in recent months that it seems unlikely to be the work of independent operators alone. “Three to five years ago, activity was almost quite basic. There was an awful lot of noise but it was fairly easy to repel if you had your wits about you,” says Owen. “During the past 12 to 18 months, the nature of the attacks emanating from the Chinese electronic network is much greater [and] advanced, in terms of style and format and the tools they are using.” Finjan has seen what Ben-Itzhak describes as near “cutting edge” malware techniques – including zero-day attacks, sophisticated obfuscation techniques and encryption techniques – that are designed to bypass even best-in-class security systems. But it is also the strategic sophistication of the attacks that is concerning, adds Owen. “The worrying thing is the intelligence of attack as opposed to the advancement of tools.”

At what price?

If the web is already proving a major threat, providing a channel for agents in China to target, attack and steal precious IP and sensitive data from Western businesses, then operating within China is certainly no safer. According to the Business Software Alliance (BSA), for example, piracy rates in

According to a well-placed source from an intellectual property body, which has also been working closely with government departments in both Hong Kong and

Technology companies in particular are believed to be targets of this activity. This was boldly asserted by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission in November 2007. In its report, the committee noted the country’s suspiciously impressive gains in technology development, both at an impressive

pace and with impressive quality. The conclusion could only be that the gains were being made at the expense of Western commerce. Indeed, so coveted are the secrets of Western high-tech organisations and infrastructure providers that representatives from the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure will only travel to China with a blank laptop, reveals Deloitte’s Owen. “Are they paranoid, or is that an informed view?” he asks rhetorically.

In many respects, identifying the perpetrators of this activity is pointless. In all likelihood, the activity unfolds in three tiers, says Prolexic’s Sop: “Military, state-sponsored and rogue – perpetrated by either politicised groups of individuals operating independently or by cyber criminals motivated by financial gain.”

In many instances, there might be a chain of command that reaches from the government itself or rogue elements in the government. Greg Day, an analyst at McAfee who oversaw the research into the Virtual Criminology Report, does not believe that the government is the chief architect of malicious code, for example. Rather, he suggests, “they are contracting it out”. There is a “big gene pool” from which to choose, he adds.

Either way, it says something fundamental about the present state of the Chinese socio-economic, cultural and legal ecosystem that IP and sensitive data is so sought after, garners such a high price and is so badly protected by the state. Fuelling a juggernaut of an economy clearly requires a significant level of dispersed information appropriation that could, in time, hugely disadvantage Western businesses and the economy at large. The desire to become a supreme economic force also seems to bring with it the desire for military, and therefore cyber, dominance, a status that seems not only to support espionage and data theft, but that will inevitably pose a theoretical threat to Western nations’ security, particularly on the mind-boggling scale on which China operates in general. In information security – be it for good or bad – scale is necessarily a significant advantage.

Nonetheless, many commentators believe that a transition in

Further reading

China’s offshore opportunity The Chinese IT outsourcing industry has many challenges to overcome. But it also has the resources to pull it off

China’s blueprint for cyber war The plan forms part of an “aggressive push” by Beijing to achieve electronic supremacy by 2050

China hacks UK government China’s military has made no secret of its desire to ramp up its information warfare strategy