The surveys are encouraging. According to a survey from Ricoh Europe, 57% of European workers believe that technology will bring about a four-day working week in the near future as it improves their productivity and efficiency.

Of course, you can be cynical and say ‘oh how very European, no wonder the region is in economic decline.’

Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, by contrast, recently spoke in favour of the 996 week, that’s nine in the morning to nine in the evening, six days a week. “If you do not do 996 when you are young, when will you? Do you think never having to work 996 in your life is an honour to boast about?” He said at an internal event.

In fairness to Ma, he does advocate play, too. At a company ‘mass wedding,’ you know those events we go to all the time, he also advocated 669, he advocated having sex ‘six days, six times, with duration being the key.’

Maybe if we all did that, but perhaps without the need for company supervision, there might be less mental health issues.

There could be another solution to poor mental health in the workplace. Now sociologists at Cambridge and Salford universities have found that working helps mental health, but apparently the optimal amount of work a week is eight hours.

AI won’t destroy jobs it will transform them

The chorus of voices claiming that AI won’t destroy jobs is getting louder

It seems a tad optimistic

An eight hour week may never be feasible, but what about all these experiments currently in progress concerning working a four day week?

For example, Berlin-based project management software company Planio introduced a four-day week for their staff last year, while UK medical research charity the Wellcome Trust conducted a feasibility study on the four-day model before eventually deciding not to go ahead.

The key lies with productivity and productivity growth in the West has been lousy for just about all of this decade.

It may be a temporary problem, of course, a lull before the fourth industrial revolution starts to transform the way we work.

Another argument made in favour of the four day week is that by having more time, we are energised and thus more productive.

The Ricoh survey found that the key to increasing productivity lies with encouraging staff to acquire new skills. Seven in 10 workers say they expect to have to upskill throughout their career, while 63% think that technology should play a central role in helping them work to the best of their abilities.

Thank God it’s Monday: Can automation really make us love our jobs again?

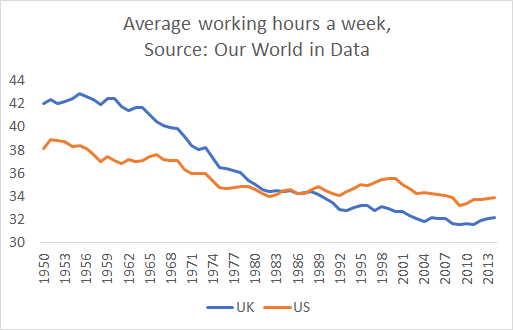

The trend is confusing. Between 1950 and the mid-noughties it was down. The average length of the working week in the UK fell from 42 hours to 31.8 hours in 2000, but since then it has been rising, back up to over 32 hours.

But for many of us, it feels like longer — how many times do you check your email at weekends, or just before going to bed? Smartphones are great and all, but they do make it hard for us to switch-off. If you work with people from time zones across the world, there’s the constant ping of WhatsApp updates or messages on Slack throughout the night.

Maybe the only solution to that is the discipline to ignore your smartphone at certain times.

But might technologies such as RPA support shorter working weeks?

Or is it possible that a good compromise would be that technology makes work more fun? After all, Jack Ma also said: “If we find things we like, 996 is not a problem, but if you don’t like [your work], every minute is torture.”

On this theme, Bruno Ferreira, UK Area Vice President at UiPath, had something to say: “Many employees work 50,60, 70 or even more hours a week, and this naturally has a knock-on impact on overall workplace happiness. Readdressing the work/life balance is a sure-fire way of ensuring happier, more relaxed staff, and automation can play a key role in this. RPA, in particular, helps keep employees happy and engaged by ensuring that mundane and admin-related tasks are carried out autonomously, freeing up human workers for higher-value and more creative tasks. More than two-thirds of UK employees are still bogged down in daily tasks — which could be undertaken by software robots, reducing pressure on human workers. With our research also showing that RPA reduces manual errors, it’s a win-win for employees and their employers.”

Then again, a four day week might be rather bodacious, perhaps just a few more public holidays would be a good start.

Will technology really destroy jobs? Amber Rudd reckons automation is driving the decline of banal

Let’s leave you with some thoughts:

“For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich to-day, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!” John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, 1930.

“The labouring man will take his rest long in the morning; a good piece of the day is spent afore he come at his work; then he must have his breakfast, though he has not earned it at his accustomed hour, or else there is grudging and murmuring; when the clock smiteth, he will cast down his burden in the midway, and whatsoever he is in hand with, he will leave it as it is, though many times it is marred afore he come again; he may not lose his meat, what danger soever the work is in. At noon he must have his sleeping time, then his bever in the afternoon, which spendeth a great part of the day; and when his hour cometh at night, at the first stroke of the clock he casteth down his tools, leaveth his work, in what need or case soever the work standeth” — James Pilkington, Bishop of Durham, ca. 1570.