North Korean’s leaders and ruling elite are actively engaged in Western and popular social media, regularly read international news, use many of the same services such as video streaming and online gaming, and above all, are not disconnected from the world at large or the impact North Korea’s actions have on the community of nations.

This according to in-depth research of North Korea’s internet activity by Recorded Future and Team Cymru, which concluded that attempts to isolate North Korean elite and leadership from the international community are failing.

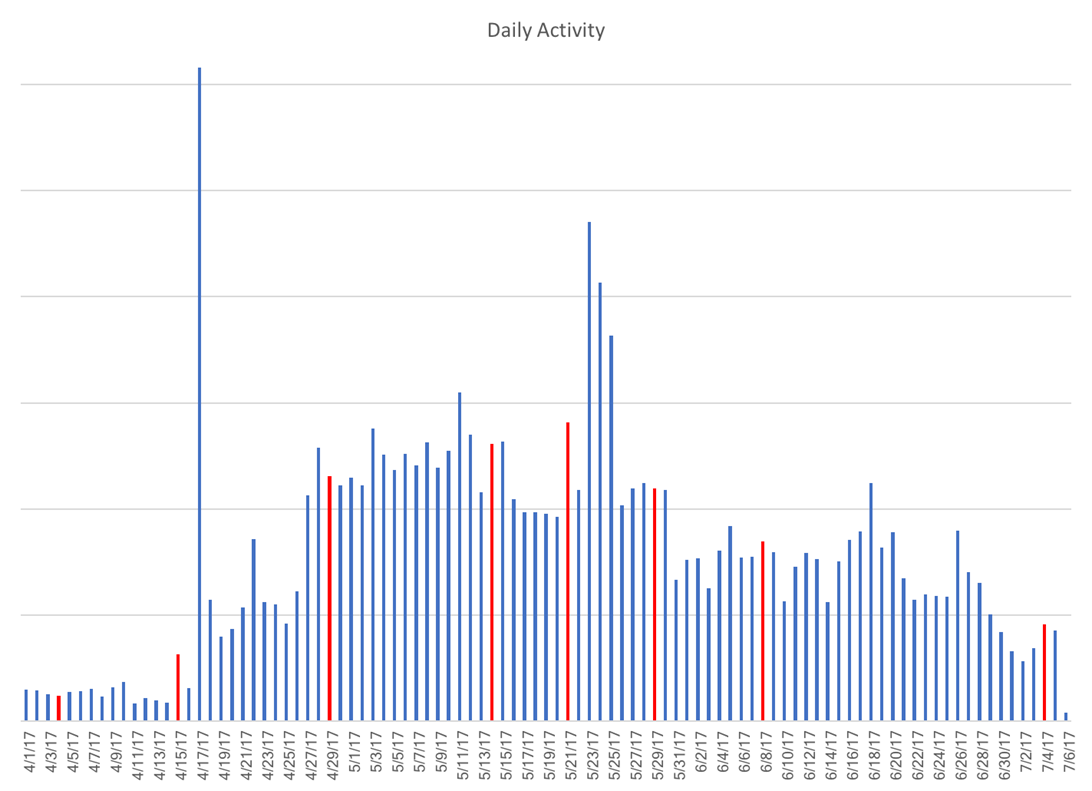

The data set reviewed suggests that general internet activity in North Korea may not provide early warning of a strategic military action, contrary to conventional hypotheses. If there is a correlation between North Korean activity and missile tests, it is not telegraphed by leadership and ruling elite internet behaviour.

The study also found that North Korea is not using territorial resources to conduct cyber operations and most state-sponsored activity is likely perpetrated from abroad, which presents an opportunity to apply asymmetric pressure on the Kim Jong-un regime.

South Korean media assesses that there may be as many as 4 million mobile devices in North Korea. So while mobile devices are widespread in North Korea, the vast majority of North Koreans do not have access to the internet.

Mobile devices (see image of a North Korea-made device below) sold to ordinary North Koreans are enabled with minimal 3G services, including voice, text messaging, and picture/video messaging, and are restricted to operating only on North Korea’s domestic provider network, Koryolink.

A small minority of users, such as university students, scientists and select government officials, are allowed access to North Korea’s domestic, state-run intranet via common-use computers at universities, libraries and internet cafes.

The network, called Kwangmyong, is slowly making its way into homes of better-off citizens, according to to Slate: “It houses a number of domestic websites, an online learning system, and email. The sites themselves aren’t much to get excited about: they belong to the national news service, universities, government IT service centers, and a handful of other official organisations. There’s also apparently a cooking site with recipes for Korean dishes.”

Among the select few with permission to use the country’s intranet are an even slimmer group of the most senior leaders and ruling elite who are granted access to the worldwide internet directly. While there are no reliable numbers of North Korean internet users, reporters estimate anywhere from “only a very small number” to “the inner circle of North Korean leadership” to “just a few dozen families.” Regardless of the exact number, the profile of a North Korean internet user is clear; trusted member or family member of the ruling class.

There are three primary ways North Korean elites access the internet. First is via their allocated .kp range, 175.45.176.0/22, which also hosts the nation’s only internet-accessible websites. The second is via a range assigned by China Netcom, 210.52.109.0/24. The netname “KPTC” is the abbreviation for Korea Posts and Telecommunications, Co, the state-run telecommunications company. The third is through an assigned range, 77.94.35.0/24, provided by a Russian satellite company, which currently resolves to SatGate in Lebanon.

Recorded Future and Team Cymru’s research only looked at data from internet use by North Korea’s ruling elite, not from intranet activity by the larger group of privileged North Koreans permitted access to Kwangmyong or diplomatic and foreign establishments that are located in North Korea.

In the early hours of April 1, 2017, as many in the West were just waking up, checking email and social media, a small group of North Korean elites began the day in much the same manner. Some checked the news on Xinhua or the People’s Daily, others logged into their 163.com email accounts, and some streamed Chinese-language videos on Youku and searched Baidu and Amazon.

Recorded Future’s analysis of this limited-duration data set demonstrates that the limited number of North Korean leaders and ruling elite with access to the internet are much more active and engaged in the world, popular culture, international news and contemporary technologies than many outside North Korea had previously thought.

The data reveals that North Korea’s leadership and ruling elite are plugged into modern internet society and are likely aware of the impact that their decisions regarding missile tests, suppression of their population, criminal activities, and more have on the international community. These decisions are not made in isolation, nor are they ill-informed as many would believe.

Patterns of use mirror Western users

North Korean elite and leadership internet activity is in many ways not that different from most Westerners, despite the extremely limited number of people who can access the internet; the relatively few numbers of both computers and IP space from which to reach it; the linguistic, cultural, social, and legal barriers; and sheer hostility to the rest of the world.

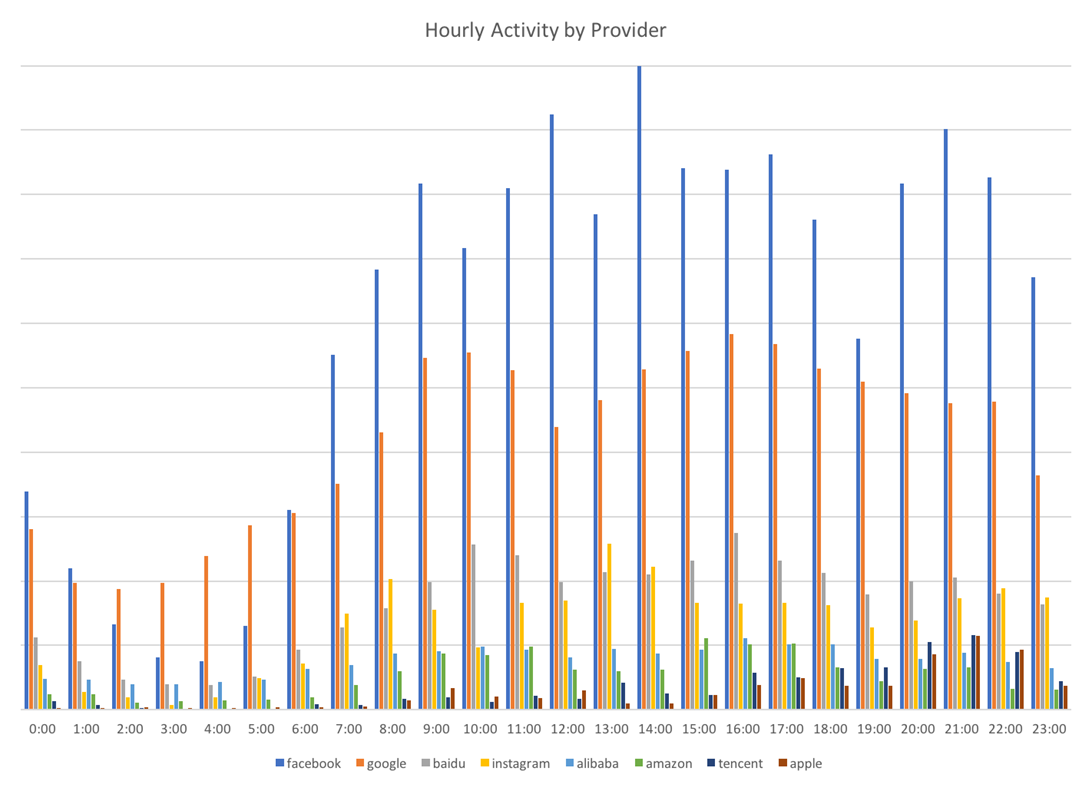

For example, similar to users in the developed world, North Koreans spend much of their time online checking social media accounts, searching the web, and browsing Amazon and Alibaba.

Facebook is the most widely used social networking site for North Koreans, despite reports that it, Twitter, YouTube and a number of others were blocked by North Korean censors in April 2016.

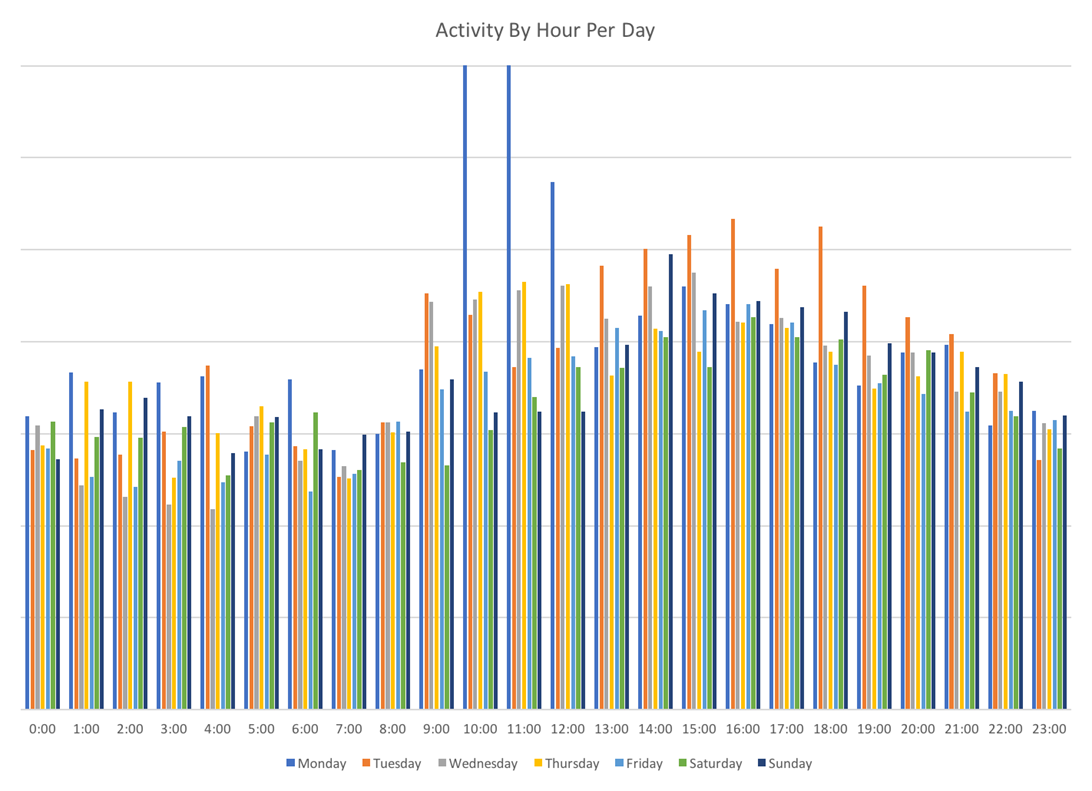

Additionally, North Koreans have distinct patterns of daily usage over this period as well. On weekdays, times of highest activity are from approximately 9am through 8 or 9pm, with Mondays and Tuesdays being the days of consistently highest activity.

Not an early warning for missile activity

Many researchers and scholars have hypothesised that there may be a connection between North Korean cyber activity and missile launches or tests. In particular, that we may be able to forecast or anticipate a missile test based on North Korean cyber or internet activity.

While the researchers in this case were not able to examine levels of North Korean malicious cyber activity, for this limited time period using this data set, there does not appear to be a correlation between North Korean internet activity at large and missile tests or launches.

This current data set is too short a duration of time to apply any long-term conclusions about the utility of internet activity as a warning device for missile tests. However, the analysis suggests that if there is a correlation between North Korean activity and missile tests, it is not telegraphed by leadership and ruling elite internet behavior.

Presence in foreign countries

The near absence of malicious cyber activity from the North Korean mainland from April to July 2017 likely indicates that, for the most part, they are not using territorial resources to conduct cyber operations and that most state-sponsored activity is perpetrated from abroad.

This is a significant operational weakness which could be exploited to apply asymmetric pressure on the Kim regime, limit current North Korean cyber operational freedom and flexibility, and reduce the degree at which they are able to operate with impunity.

This data and analysis demonstrate that there are significant physical and virtual North Korean presences in several nations around the world — nations where North Koreans are possibly engaging in malicious cyber and criminal activities. These nations include India, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nepal, Kenya, Mozambique, and Indonesia.

The datasets in the research demonstrate that North Korea has a broad physical and virtual presence in India. Characterised by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs as a relationship of “friendship, cooperation, and understanding”, the analysis supports the reports of increasingly close diplomatic and trade relationship between India and North Korea.

Patterns of activity also suggest that North Korea may have students in at least seven universities India and may be working with several research institutes and government departments. Nearly one-fifth of all activity observed during the time period involved India.

North Korea also has substantial and active presences in New Zealand, Malaysia, Nepal, Kenya, Mozambique and Indonesia. Our source revealed not only above-average levels of activity to and from these nations, but to many local resources, news outlets and governments, which was uncharacteristic of North Korean activity in other nations.

It has been widely reported that North Korea has a physical presence to conduct cyber operations in China, including co-owning a hotel in Shenyang with the Chinese from which North Korea conducted malicious cyber activity. Nearly 10% of all activity observed during this timeframe involved China, not including the internet access points provided by Chinese telecommunications companies.

The analysis found that the profile of activity for China was different than the seven nations identified above, mainly because North Korean leadership users utilised so many Chinese services, such as Taobao, Aliyun, and Youku, which skewed the data.

After accounting for use of Chinese internet services, which of course do not signify either physical or virtual presence in China, the pattern of activity to local Chinese resources, news outlets and government departments mirrored the seven previously identified nations.

The researchers said it is “highly likely” that North Korea is conducting cyber operations from third-party countries. “We are not implying that the governments of these seven nations identified above, excluding China, are complicit with, supportive, or even knowledgeable of the North Korean presence in their country,” they said.

Insights into internet use

The research shows that many of North Korea’s ruling elite utilise VoIP services to talk and message others overseas. Others have AOL accounts and checked them regularly. Some users frequent beauty and health sites. Others purchase expensive sneakers online. Many investigate industrial hardware and technology optimisation services.

During the analyses period, some users spent time every day researching cybersecurity companies and their research, including Kaspersky, McAfee, Qihoo360 and Symantec, and DDoS prevention companies and technologies such asDoSarrest and Sharktech. One user received training on the use of THURAYA and satellite communications equipment and others researched the physics and engineering departments at several Malaysian, U.S., and Canadian universities.

Gaming and content streaming accounted for 65% of all internet activity in North Korea. Broadly, users consume content mostly from the Chinese video hosting service Youku, iTunes, and various BitTorrent and peer-to-peer streaming services. For games, North Korean users seem to prefer games hosted by Valve and a massively multiplayer online game called World of Tanks.

Suspect activity

While the majority of activity from North Korea during this timeframe was not malicious, there was a smaller but significant amount of activity that was highly suspect. One instance was the start of Bitcoin mining by users in North Korea on May 17.

Bitcoin mining is difficult because it is a computationally complex task and can require up to 90% of a machine’s power. The benefit to using all of this energy and adding the transaction records to the blockchain is that each miner is awarded not only the fees paid by the users sending the transaction, but 25 bitcoins once they discover a new block.

Before that day, there had been virtually no activity to Bitcoin-related sites or nodes, or utilising Bitcoin-specific ports or protocols. Beginning on May 17, that activity increased exponentially, from nothing to hundreds per day.

The timing of this mining is important because it began very soon after the May WannaCry ransomware attacks, which the NSA has attributed to North Korea’s intelligence service, the Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB), as an attempt to raise funds for the Kim regime.

By this point (May 17) actors within the government would have realised that moving the Bitcoin from the three WannaCry ransom accounts would be easy to track and ill-advised if they wished to retain deniability for the attack.

It is not clear who is running the North Korean bitcoin mining operations, but given the relatively small number of computers in North Korea coupled with the limited IP space, it is not likely this computationally intensive activity is occurring outside of state control.

Additionally, during this time frame it appeared that some North Korean users were conducting research, or possibly even network reconnaissance, on a number of foreign laboratories and research centres.