Founded 16 years ago, Ocado has revolutionised the grocery industry with its online and mobile delivery services and highly automated warehouses. It now has more than 12,000 employees and is the world’s largest online-only grocery retailer.

One of its first employees was Anne Marie Neatham, who is now COO at Ocado Technology, the technology division that powers Ocado and in which more than 900 employees sit.

Neatham joined Ocado in 2002 as one of its first hires to lead the development of its early in-house support applications. She has since led the development of applications in various areas of Ocado and managed the opening of Ocado’s first international development centre in Poland. She leads a variety of technical development and infrastructure departments and looks after development centres in Kraków, Wrocław, Sofia, Barcelona and the UK.

‘When I joined Ocado, what was so appealing about it was that they were blatantly trying to change the way we shop,’ says Neatham. ‘I don’t like supermarket shopping so I was incentivised to think about alternatives. Also, I had done online shopping with one or two of the big supermarkets and I didn’t think it was done very well.’

>See also: How will the UK adapt to the Fourth Industrial Revolution?

From the beginning, the online retailer sought to differentiate itself as a technology and solutions company that happened to deliver groceries. Achieving this required an enormous and complex technology setup, nearly all of which was built in-house.

Ocado started with a highly manual warehouse but has since built the world’s biggest automated warehouses.

‘When I started, I think they’d realised very quickly that they weren’t going to be able to buy off-the-shelf solutions because nobody was doing it the way they wanted to do it,’ says Neatham. ‘That’s when they started to bring in technologists and people who had a technical background. I had a mixed bag of skills, and so did everybody else who joined. We were all driven to produce new solutions to solve existing problems.

‘Food is quite complicated because it needs to be kept at different temperatures and comes in different shapes and sizes. Nobody else could solve the logistics problem of selling well to the customer front door so we were very keen to create solutions that were, and continue to be to this day, pretty revolutionary in terms of the technology and application and how far we were willing to push the envelope.’

Ocado’s technology estate today is broad and deep, encompassing real-time control systems, IoT, robotics, machine learning, simulation, data science, forecasting systems, routing systems, inference engines, big data and more.

Robots place the chosen items on high-speed conveyor belts that take them to attendants, who then pack them into shopping bags. Further technology alerts them if an incorrect item is packed, while a computer program tells drivers the best delivery routes to service 580,000 active customers.

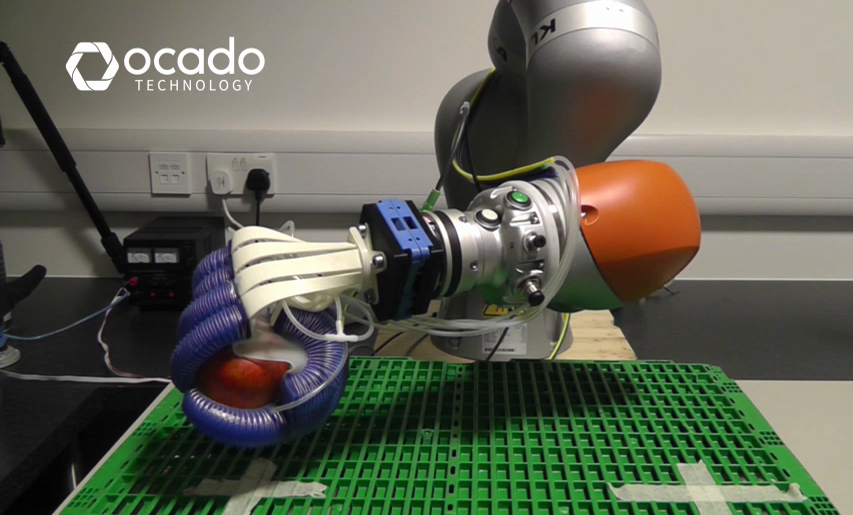

One of Ocado’s latest innovations in development is a robotic hand for grocery picking. The Ocado Technology robotics team is working with a hand capable of safely grasping a wide variety of products, including many from Ocado’s current range, which includes over 50,000 hypermarket items.

To avoid damaging sensitive and unpredictably shaped grocery items, the robotic hand uses the principle of environmental constraint exploitation to establish a carefully orchestrated interaction between the hand, the object being grasped and the environment surrounding the respective item.

‘It’s a big project for us, and there is no reason why it shouldn’t work,’ says Neatham. ‘But what we’re looking for in a robotics hand is something that is very reliable, that can pick up different products and won’t damage them. Most of the robotic hands you see in other organisations do the same function again and again, but a six-pack of Evian water is very different to an orange. The way we treat each item is very different, and the temperature at which the robotic arm will work is very different.

Long-term plan

The day Ocado can replace all of the pickers in its warehouses is a long time away, Neatham admits, because of the necessity for treating different types of goods and products in different ways. However, Ocado will start to use the robotic arm in areas where repetitive items are quite similar.

‘We pick over a million items in each of our warehouses every day, and as an organisation we will be picking 3 to 4 million items a day very soon, so the more we can automate the better,’ says Neatham.

Other ongoing Ocado projects include its highly automated Andover warehouse, which involves hundreds of robots swarming on a grid the size of several football pitches. Ocado Technology is also a coordinator of the SecondHands project, which aims to design a collaborative robot that can learn from and offer assistance to warehouse maintenance technicians in a proactive manner.

Ocado has recently applied for a patent for a modular system for shipping standardised boxes that align over a grid and can morph on demand and be transported on trucks and ships. ‘If we can pick, store and move all of our items quickly, automatically and very efficiently, that will increase our profitably,’ says Neatham.

Needless to say, that profitability will come from Ocado’s reduced need for manual labour. But Neatham is keen to point out that technologies like robotics and AI will more than just replace people who handpick things.

‘I think we are going to experience another industrial revolution – and it’s going to happen in every role,’ she says. ‘If you look at AI, it’s going to add an awful lot in fields that we previously thought needed a human brain. Very possibly, an awful lot of the sifting through information will be done by machines.’

>See also: CIO Spotlight: Paul Clarke, director of technology, Ocado

To help people prepare for the rise of automation in the workplace, Ocado created a ‘Code for Life’ initiative to help drive an ‘educational revolution’ that gives teachers the tools to teach children to code.

Key Stages 1 and 2 (children aged five to nine) are covered by Ocado’s Rapid Router game, which children can play in the classroom as well as at home. The game allows children to program with ‘code blocks’ on screen, similar to Lego, without having to directly program. As children progress through the levels of the game, children learn programming principles and finish with programming in Python.

‘The world is changing, and that pace is going to speed up rather than slow down,’ says Neatham. ‘I think the change is mostly for the good, but obviously we have to respond to it and acknowledge the fact that we need to adapt and change, because it will leave some people behind if we don’t.’