The Netherlands has Europe’s busiest railway network. For every kilometre of track in the network, 20,000 kilometres of train travel take place every year, more than double the EU average. This tight but busy network requires highly efficient planning, and technology lies at the heart of that efficiency – more specifically, a heavily customised optimisation software implementation from ILOG, the IBM-owned software vendor.

This technology, explains Erwin Abbink, business consultant with the country’s public rail operator, Netherlands Rail, supports a sophisticated carriage allocation system that uses complex arithmetic to create the ‘perfect’ timetable for rolling stock – essentially, matching carriages to passengers.

“We operate 5,000 trains a day and 10,000 to 12,000 trips, to which we assign rolling stock units,” Abbink explains. “The idea is to match the number of rolling stock units to the number of passengers in the best way. You don’t want a shortage of seats for passengers, and you don’t want empty seats because that’s really expensive.”

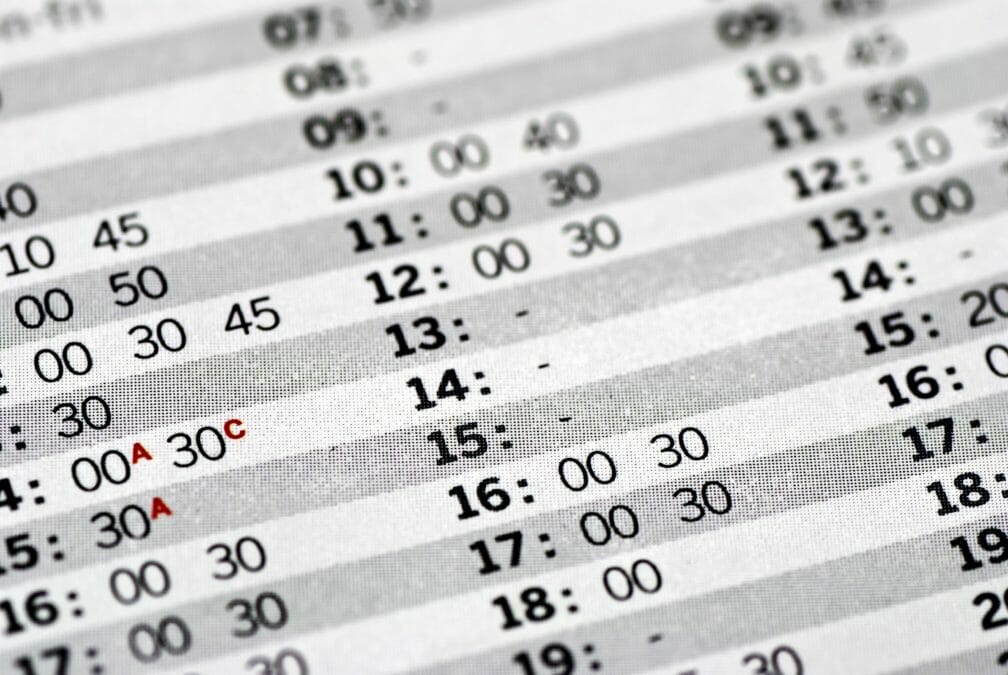

Incredibly, this process was conducted manually until a few years ago, he explains. “It was a big piece of paper with a timetable and people who used stencils and lines to make plans by hand. It was labour intensive and not optimal.”

The ILOG project began in the late 1990s with the hopes of improving that system, with help from the centre for mathematics and computer science at Amsterdam University. But it took several years to develop, and it wasn’t until around 2005 that the project “got to the point where we could solve the most difficult problems we had.”

The academic input was vital because the ILOG technology was not up to the task straight out of the box. “The ILOG tool is really powerful but unless you do really special tricks with it, it can’t solve the problem,” Abbink says. “Our problem is unique and you can’t solve it by approaching it in a straightforward way, which is why we needed smart people from the university.”

Even when the model worked, it ran into opposition from existing planners, who felt the technology was muscling in on what they regarded as an artisan craft. “The planners would violate all kinds of rules saying ‘we can make better plans’, but they weren’t better plans, they just thought they were,” Abbink says.

“There has always been a struggle between planners and the new system.” The stakes in this project go beyond simply reducing operating costs: in 2015 the Dutch government decides whether the rail company keeps its concession to run the main tracks in the Netherlands.

“The most important thing [to retain the concession] is public opinion. There is a trade-off between efficiency and service – so we need to deliver more seating at the same cost,” Abbink explains. The railway is also at the mercy of external factors, such as the price of fuel: when fuel is cheap, people drive rather than take the train.

“There’s also been a decrease in the number of commuters going to work,” says Abbink. Compensating for these factors quickly is therefore crucial for planning the right level of service.

And even the planners now acknowledge that the flexibility of the new system is impressive. “It used to take several months or even a year to make a new plan,” Abbink says. “Now it only takes one night or a few days. If the number of passengers decrease, we can react very quickly.”