As electronics and related code become more integrated into modern vehicles, we are reaching a point where they will require similar protection as smartphone, tablets and traditional computers.

There is a real worry about hackers controlling vehicles in scenarios such as having fun with the songs being played, downloading rogue apps, disabling the vehicles ignition, or overriding braking systems.

Similar to the early days of the internet, security has not received a great deal of attention to date from car manufacturers. Researchers have demonstrated in controlled experiments that vehicles can be controlled via the telematics systems at great distances and they have successfully embedded malware over wireless connections.

Modern smart cars in general are becoming more susceptible to electronic attacks, which can be more effective than previous ‘slim jim’ type brute-force car opening attacks.

>See also: Is the UK self-driving itself towards a security nightmare?

In recent weeks, it has been disclosed that a £15 wireless device can be purchased online which amplifies a modern car’s wireless entry system so that the signal travels from the thief’s device to the owners keys up to 100 yards away, allowing them access to the car and drive away in seconds.

Finally, a risk associated with rolling out technology in smart cars, as opposed to other platforms, is the potential of distraction leading to accidents due to poor design or malfunctions.

Technology experts outside of aviation and medical products tend not to follow stringent testing methodologies but lazily rely on fixing problems as they arise. Therefore a misconfigured service in a fast-moving smart car can lead to death.

A number of factors may lead to change however. The motivation to build rigorous and secure systems should be there because it is quite possible that all involved in its design could be held liable if a defect caused or even contributed to a collision.

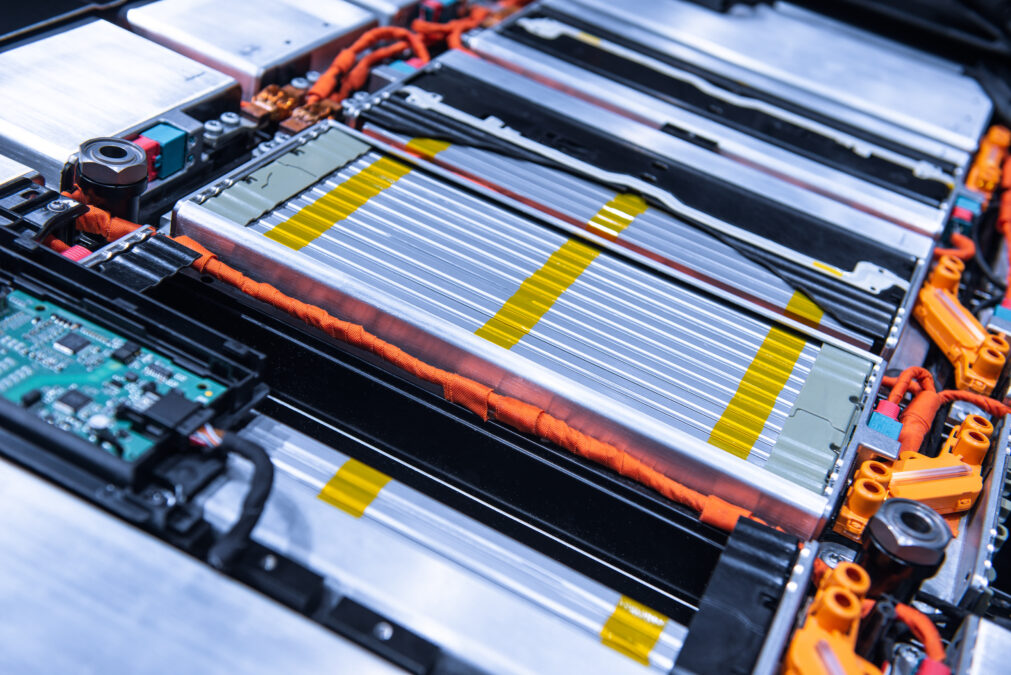

Vehicles have evolved to contain a complex network of as many as 100 independent computers, known as electronic control units (ECUs).

ECUs perform a variety of functions such as measuring the oxygen present in exhaust fumes and adjusting the fuel-oxygen mixture to improve efficiency and reducing pollutants.

Gradually, these ECUs have become integrated into nearly every aspect of a vehicle’s functioning, including steering, cruise control, air bag deployment and braking.

In an article published in IEEE Spectrum, the authors stated that an “S-class Mercedes-Benz requires over 20 million lines of code alone” and “has nearly as many ECUs as the new Airbus A380 (excluding the plane’s in-flight entertainment system)”.

They estimated that vehicles will soon “require 200 million to 300 million lines of software code”. This, more than any other statistic, must surely demonstrate the vulnerable nature of the 20th century vehicle.

In addition, not only do these ECUs connect to each another, but they now can connect to the internet – making vehicle computers as vulnerable to the same digital dangers widely known among other networked devices: trojans, viruses, denial-of-service attacks and more.

It is quite common for new vehicles to have numerous connectivity modes such as through cell phone networks and to the internet via systems including OnStar, Ford Sync and others.

They have Bluetooth connectivity, short-range wireless access for key fobs, and tyre pressure sensor. Some support satellite radio and they also have inputs for DVDs, CDs, iPads and USB devices.

One of the earlier hacking studies was done by the Centre for Automotive Embedded Systems Security, the Washington team that was able to bring a wide range of systems under external control, such as the engine, brakes, locks, instrument panel, radio and its display.

The attackers posted messages, initiated annoying sounds and even left the driver powerless to control radio volume. They also attacked the Instrument Panel Cluster/Driver Information Centre, displaying cheeky messages, altered the fuel gauge and speedometer readings, and adjusted panel illumination.

Subsequent hacks took over the Engine Control Module, which led to uncontrollable engine revving, readout errors and complete disabling of the engine.

Lately, Chrysler jeeps have been hacked from many miles away. The almost-universal controller area network (CAN) bus on vehicles makes such breaches possible.

All modern vehicles possess an ‘on-board diagnostics’ port that allows mechanics to diagnose faults and retrieve information on the vehicle’s performance, and in some cases change aspects such as the timing of the engine.

>See also: The revolutionary road to autonomous driving

This is becoming the main access point for hackers as everything can be changed using this port. Yes, important aspects such as the speed control, steering and brakes are all located on a separate vehicle network – there is still interconnectivity between both vehicle network backbones so that a breach in one can cause havoc in the other.

It is presently still a difficult system to breach but as more and more exploits are shared on the internet, there is much cause for worry.

The vehicle mobile phone hardware providing a connection to the on-board computer system is also vulnerable to malware being installed that could allow a thief to unlock the car remotely and steal it. This is serious as there is already talks of an app store for vehicle apps.

Sourced from Dr Kevin Curran, senior member of the IEEE and lecturer at the University of Ulster