New laws and regulations in Russia require companies to store the personal data of Russian citizens on Russian territory, and impose certain other controls and limitations on websites and foreign investments in media.

While controversial, these rules reflect the increased attention of the Russian authorities to the digital world, and to the media sector generally. International companies who are active in the Russian market have scrambled to determine the appropriate response to the new rules, including potential adjustments in their business and technical platforms.

Local storage law

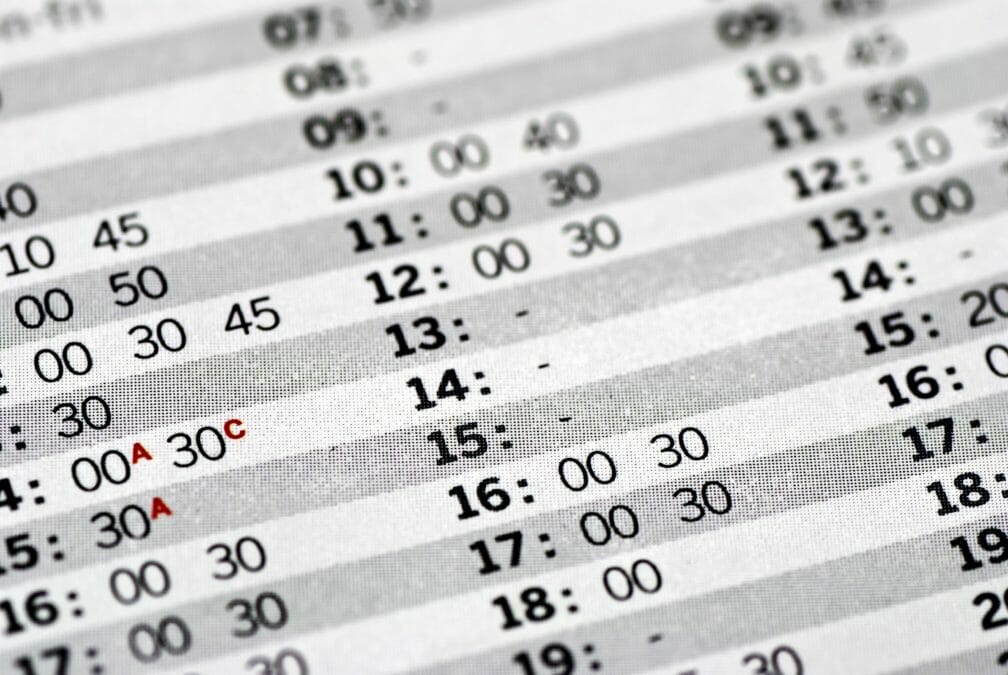

In July 2014, the Russian State Duma approved amendments to the Russian Personal Data Law to include local storage requirements (the ‘Local Storage Law’). Initially, the Local Storage Law was due to come into force in September 2016, however, the deadline was later moved up to September 1, 2015.

The amendment itself reads as follows: ‘when collecting personal data, data operators must use databases located in Russia to record, systematise, accumulate, store, amend (update and change) and extract personal data of Russian citizens’.

> See also: EU Data Protection Legislation: what about employee data?

As one may no doubt appreciate, such brief language raises a number of interpretation issues, including very practical ones, for example, clarifying what a ‘database located in Russia’ means and the method by which companies should verify the nationality of their users to determine whether personal data come from Russian citizens or not.

However, the most important question is whether the Local Storage Law applies to international companies. The general consensus among experts is that companies with no corporate presence in Russia (either in the form of a subsidiary, a branch or a representative office) should not be covered by the law.

At the same time, online businesses with no local presence could still be affected, particularly if they customise their websites for Russian users or promote their services in Russia.

The second most important question is whether companies are still allowed to store personal data of Russian citizens abroad. Some experts note that the Local Storage Law does not prohibit or restrict cross-border data transfers.

Accordingly this can be interpreted to mean that once the data is collected and stored in Russia in a so-called ‘primary database’, it is then possible to transfer this data abroad, provided that the cross-border transfer complies with the general provisions of the Russian Personal Data Law. This approach has been indirectly confirmed by some Roskomnadzor’s officers during round-table discussions of the new law.

Companies affected by the Local Storage Law were required to customise their IT processes and IT systems to allow collection and recording of personal data on databases located in Russia starting 1 September 2015.

On July 16, 2015 Roskomnadzor announced that it does not plan to have any unscheduled inspections for Local Storage Law compliance until the end of 2015 so those who were not be able to meet the September 2015 deadline still have some time before Roskomnadzor starts actively enforcing the new law.

Internet Data Storage Law

In May 2014 Russia introduced a number of changes to another key statute governing the Internet sector – the Russian Information Law (the amendment has been dubbed the ‘Internet Data Storage Law’, but is also known as the ‘Blogger Law’ as it also introduced rules on bloggers). The changes came into effect on August 1, 2014.

The Internet Data Storage Law imposes new requirements for companies that organise the dissemination of information on the Internet. It is understood that the law targets, primarily, social networks and other services that allow internet users to communicate with each other.

However, the definition of ‘organisers of the dissemination of information on the Internet’ can be broadly interpreted to cover any website that allows users to leave comments or send an email to the company using a web-form.

Such ‘organisers of the dissemination of information’ must store information about website users and their communications in Russia for six months, make the stored data available to Russian law enforcement authorities and use certain hardware and software that allows such authorities to gain access to the records and monitor them.

The Russian media regulator, Roskomnadzor, keeps the register of the organizers of the dissemination of information. The companies can register voluntarily or wait until they get a notice from Roskomnadzor, in which case such registration is mandatory.

At this point around 40 companies are on the list, including the largest Russian social network, VK.com, and the largest mail service, Mail.ru. The good news is that, reportedly, Roskomnadzor is of the view that the Internet Data Storage Law applies only to those companies which are included on the register. However, this view is not yet supported by any formal clarification.

Foreign investments restrictions in mass media

The Russian Mass Media Law was amended in October 2014 to limit foreign investments in mass media to 20% starting January 1, 2016. The amendments will apply to television, radio, print and all other mass media.

Until recently the Internet sector was not especially concerned by these restrictions as the registration of a website as an instrument of ‘mass media’ – and corresponding requirements to comply with the same rules as television and radio channels – has always been voluntary. In current practice, only online versions of traditional mass media, such as radio stations or magazines, as well as some news websites typically obtain such registrations.

> See also: New EU data law’s go-live data finally revealed

However, on June 17, 2015, Izvestia – one of Russia’s largest newspapers – reported on a new initiative to make all popular websites register as mass media. If this becomes law then all online companies and websites distributing content to Russian users may potentially be affected. The potential scope is unclear at this stage.

If the Russian ‘mass media’ rules are applied to websites, this could mean that foreign citizens and companies may not control more than 20% of such websites. In addition, the content published on the websites (both by website administrators and users) may have to be reviewed for compliance with other restrictions applicable to mass media, such as child content protections, advertising restrictions and other content-based rules.

Despite these challenges, both the Internet and media sectors in Russia are relatively dynamic, with online commerce continuing to grow rapidly, and business segments such as the pay TV market continuing to grow. It is hoped that a balance can be found between the new requirements of Russian law and the needs of Internet and media businesses.