It is clear that the future of virtual reality (VR) is bright. But while Facebook’s Oculus Rift, Sony’s PlayStation VR, Samsung’s Gear and HTC’s Vive have led an overwhelming introduction to the market, it’s looking like it will be 2017 or even 2018 before the technology really gathers traction.

With this in mind, the progress can’t be left to the VR developers alone. The software and device engineers must also make a viable bridge between them, and develop platforms attractive to consumers.

People will want to explore and enjoy immersive films, casinos, shopping and games with their devices. First though, it will need to establish itself as a truly mainstream device, which didn’t happen in 2016 as planned.

There are more than a few reasons for this, including the cost of the device and the price required to provide a high-end computer capable of working in sync with the device.

>See also:The business of virtual reality

Again, this will likely be remedied before long – maybe five or six years from now, when the costs of computers with high-end graphics cards has lowered, just as the price is likely to do for the VR headsets also.

Chipset maker Nvidia predicted last December that in 2016 only 13 million PCs will be powerful enough to run VR, meaning that less than 1% of the 1.43 billion PCs in use globally this year are up to scratch. This explains the slow start.

Video games consoles are also staking a case for the future of VR, with Sony already announcing PlayStation VR headsets to be launched in October 2016. These sets are cheaper in cost than the Oculus and work in a normal PS4, but this machine will be updated into PS5 by the time VR is expected to peak in six years’ time, so time will tell on the price and success of both.

Smartphones, too, will be expecting to take their cut, helped by the specially-designed cheap mobile VR devices such as Google Cardboard, which retails below $30 and comes with a headset that smartphones slide in to, leaving phones to do the hard work for themselves.

At this point it is worth remembering that when Oculus Rift launched its $2.4 million Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign in 2013, it was billed as the first truly immersive virtual reality headset for video games.

Expectations such as this have allowed potential virtual reality to grow quickly, with revenues from both VR hardware and software products projected to be a formidable $5.2 billion USD in 2018.

At the same time, the number of users adopting the new tech, predominantly gamers, is expected to reach 171 million. At present, 43 million people worldwide own a VR headset, so ownership could rise more than three fold in just two years, even before the predicted peak in 2021.

Even allowing for a slow and tentative launch, it is a matter of when, not if, VR takes over and becomes gaming’s next big trend – so naturally it’s not only video games for mobile, console and PCs that are developing entertainment geared towards the incoming VR, but also the iGaming industry too.

In a speech at the ICE Totally Gaming fair in London earlier this year, Per Eriksson, CEO of iGaming software provider NetEnt, said 2016 had been “bigger and better than ever” for his company. NetEnt has expanded at a rate 25% annually and already claims a 31% slice of the market, so what has driven them to their best year on record? The company launched a series of VR slots games.

At the moment, these are all we have to go on, but given that slots are not the only casino games and, if anything, perhaps the one with the least to gain from VR, the fact that they have done so well bodes well for VR casinos in the future.

It is an exciting time for gaming as a whole and an intriguing one for the iGaming industry, which will hope to capitalise on online casinos’ enormous popularity.

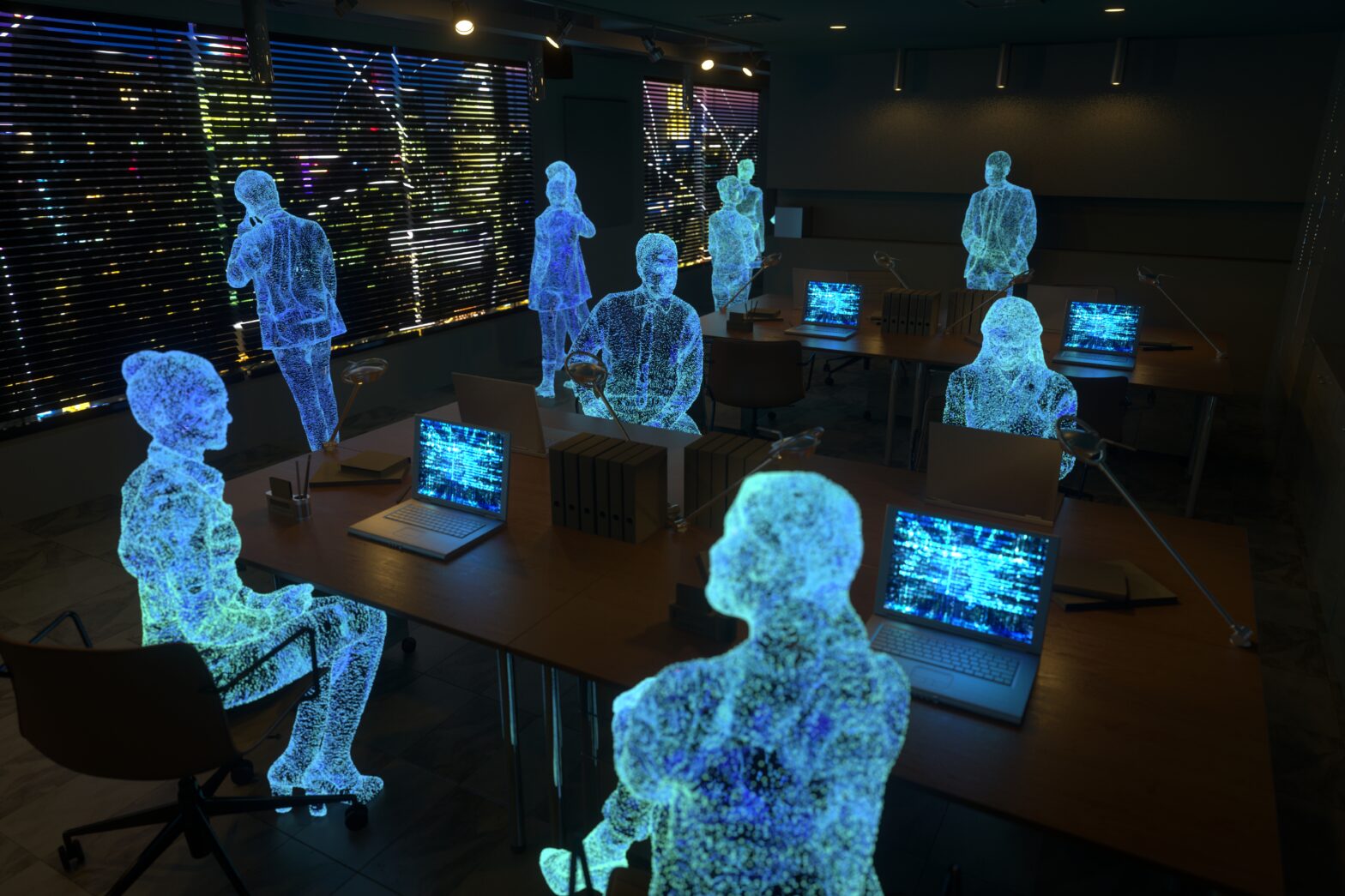

The plan is that, through a headset, players can access a casino in a virtual environment, bringing much more realism and responsive motions – like entering a casino in the real world, but from the comfort of your own living room. Walk from table to table and sample the roulette, blackjack, craps and Texas Hold’em poker. Cashing chips, chatting in real time and maybe even reading opponents tells are all abilities that would make a virtual casino more lifelike.

Goldman Sachs have already forecast that VR has the potential to out-monetise TV over the next decade and, if we were to include the predicted $80 billion VR sales figures, TV would do well to keep up with their new threat. Watch this space.

See also: What’s holding virtual reality back? – The greatest hurdle VR faces is a lack of people producing the content that VR desperately needs, due to a lack of skills