It’s common practice. Organisations are now increasingly hiring former (cyber)criminals or hackers to test their systems and make sure they are secure.

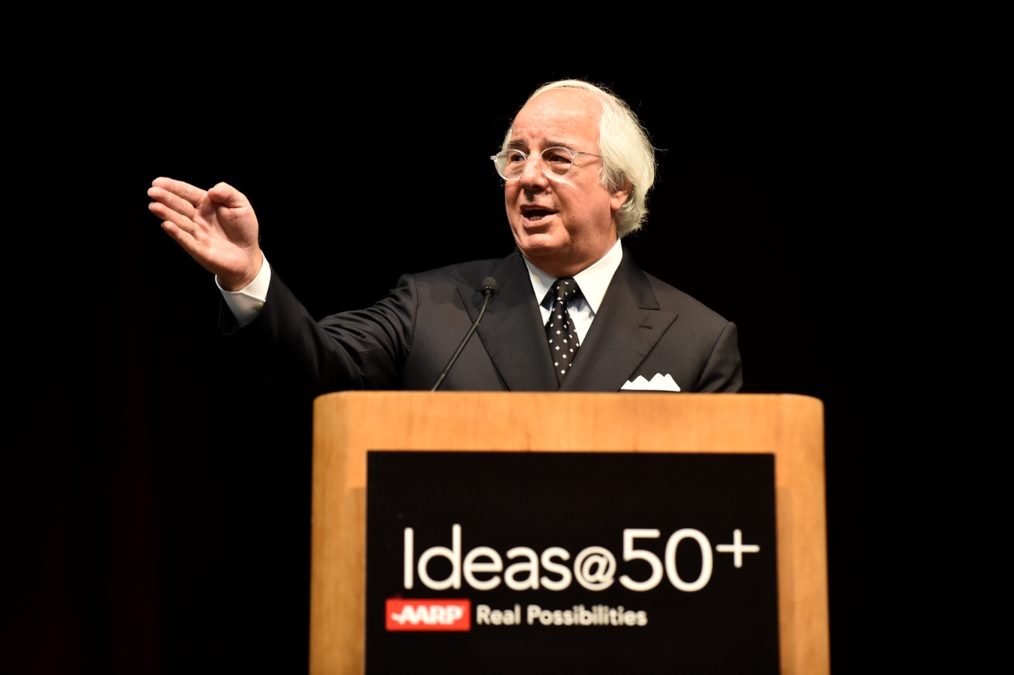

This is why, despite a long friendship spanning 20 years, Ori Eisen — CEO and founder of Trusona — sought the advice of former con man, Frank Abagnale Jr — the subject of the award-winning film, Catch Me If You Can.

“The truth is I can develop a lot of things, but I’m not a criminal. I can’t think like you can. So I don’t know how someone would defeat whatever I develop, but you do,” Mr Eisen said.

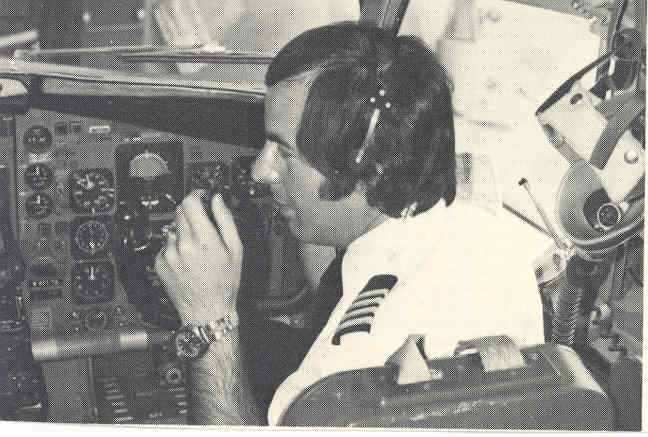

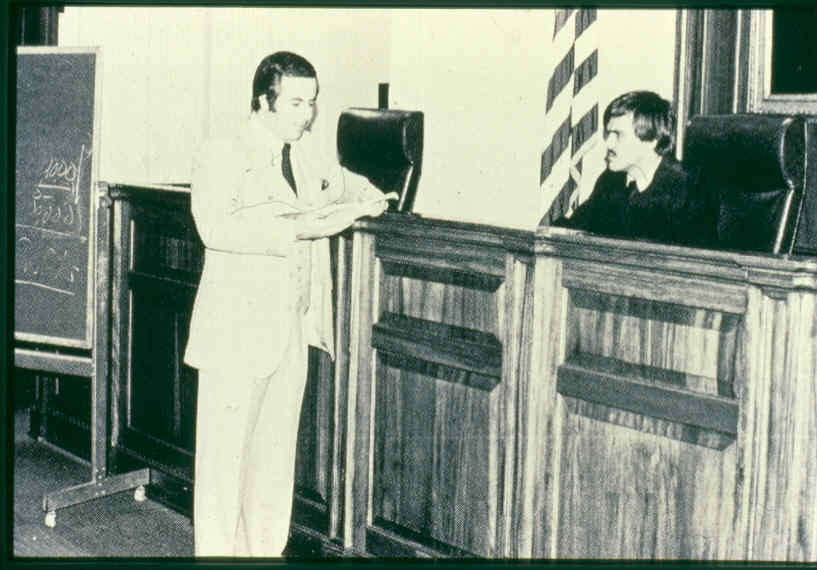

While Mr Abagnale was not a cybercriminal, his early life, between the ages of 16 and 21, were fraught with criminal activity — he impersonated a pilot, a doctor and a lawyer.

Today, however, you’d never know it. The words criminal and Frank Abagnale don’t even feel right in the same sentence.

Information Age’s guide to recruiting ethical hackers

The transition of crime from the physical to the digital

Crime today, of course, has a significant physical element. However, over the last 20 years there has been a criminal movement towards the digital. Cybersecurity Ventures predicts cybercrime damages will cost the world $6 trillion annually by 2021, up from $3 trillion in 2015.

The attack surface area is now different, but “the one thing that never changes is that criminals are all the same,” said Mr Abagnale. “So, if you think like a criminal, it doesn’t matter what they do, you can figure out there motives and means.”

Over the course of a 43-year-career in the FBI, Mr Abagnale has worked on every single data breach, including; TJX in 2007, and more recently, the Marriott and Facebook breaches.

“The one thing that I’ve learnt is that every breach occurs because somebody in that company did something that they weren’t supposed to do, or somebody in that company failed to do something they were supposed to do,” he said.

“My first 20 years at the FBI dealt with counterfeiting, forgeries, embezzlement, and the last 20 years have all been cyber” — Frank Abagnale Jr

“Hackers do not cause breaches, people do”

Indeed, “hackers do not cause breaches, people do,” explained Mr Abagnale.

“All hackers do is look for openings and there’s openings in every company.”

He pointed to the Equifax breach — the organisation didn’t update their systems, they didn’t fix the security patches sent to them by Microsoft. In this instance, the hackers got into the system and sat there for a year deciding what data to steal. After this period, they decided to steal 148 million credit reports and 12 million drivers’ licences.

“It always comes down to the human element,” reiterated Mr Abagnale. “There is no technology, there never will be any technology, including AI, that can defeat social engineering.”

In fact, organisations can only defeat social engineering through education and training.

Cyber security best practice: Definition, diversity, training, responsibility and technology

Social engineering

IBM called Frank Abagnale the father of social engineering, but by his own admission that “was kind of ridiculous”. People had been practicing the art of conning long before Mr Abagnale — perhaps not so suavely though.

However, at 16, through social engineering, that’s exactly how “I got the uniform,” he said, referring to when he impersonated a pilot. “I got on the phone, convinced them I was a pilot and they told me where to go to get the uniform. I didn’t know I was socially engineering anybody, but I only had the method of the telephone. Today, there are so many other methods of communication that people can socially engineer. So, I look at those crimes as the same thing I did 50 years ago, but just with new methods of doing it and getting the information.”

“If, when I was 16, the technology existed that exists today, I wouldn’t have stolen $2.5 million, it would have been closer to $200 million” — Frank Abagnale Jr

Cyber security will always be an issue, “until we get rid of passwords” — Frank Abagnale Jr

Crime has gone global

In his 43-year-career, the biggest surprise to Mr Abagnale is how crime has become global. Back when he started, the FBI were only dealing with criminals domestically in the United States. “For example, we get 5,000 phishing emails a day in the United States. We do track the money and about $12 billion has gone out of the economy from companies and businesses that have been phished. But when we track it, we actually find it goes out to about 155 other countries — it’s obviously criminals in other countries,” he said.

“I’m also shocked by how much greed there is. Even if tomorrow you and I did something and we made $25 million, instead of saying okay, we’re done now, we got away with this, nobody is coming after us, we’re through. They just keep doing it. And that’s why most criminals get caught; it’s not good police work, it’s the fact that they keep doing the same thing over and over again.

“Years ago, criminals and conmen had a little bit of compassion in them. So if I was ripping you off for a lot of money, I might say okay I’ve taken enough of this guy’s money, I don’t want to leave him broke in the street, I’ll move on to the next victim. How they take these people’s homes, their mortgages, their pensions, the veterans in the service who served overseas and come back, they steal their money so they have nothing. I always remind people once you lose your money, you’ll never get your money back. We may catch them, we may send them to jail for life, but you’re not going to get your money back. It’s much wiser to prevent crime than deal with crime once it’s occurred.

“I’ve always been on the side of let’s prevent it rather than go chase [or catch] people once they’ve done it. Let’s make sure they can’t do it.”