Unsung heroes helped mankind achieve the impossible, they developed the technology behind the first moon landing and the data to support the success of the Apollo 11 mission, while some of NASA’s first coders made it possible.

The first moon landing took place 50 years ago, Apollo 11 touched down on the moon’s surface. On 20th July 1969, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins (who remained in the command module and never walked on the moon) wrote themselves into the history books by doing something that, even today, is regarded as the pinnacle of human endeavour.

Those brave astronauts deserve their plaudits, but we should not forget the teams of experts on the ground whose task it was to get them into space, and back to Earth safely. Let’s look at a snapshot of some of the ground-based heroes and their innovative use of data, modelling and visualisation techniques that helped shorten seemingly mind-boggling odds against success, creating the technology behind first moon landing.

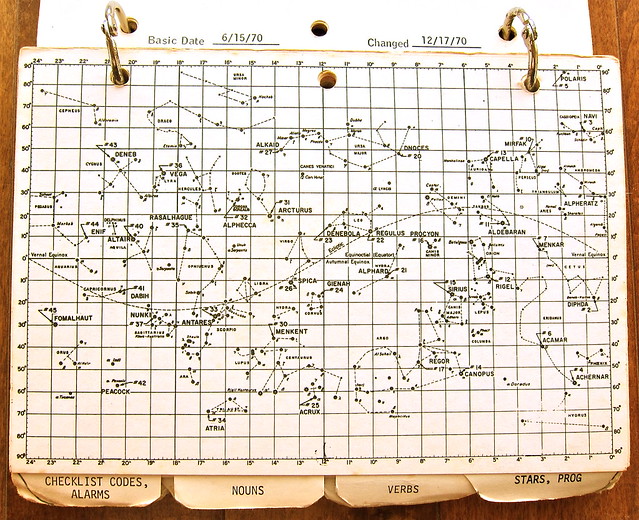

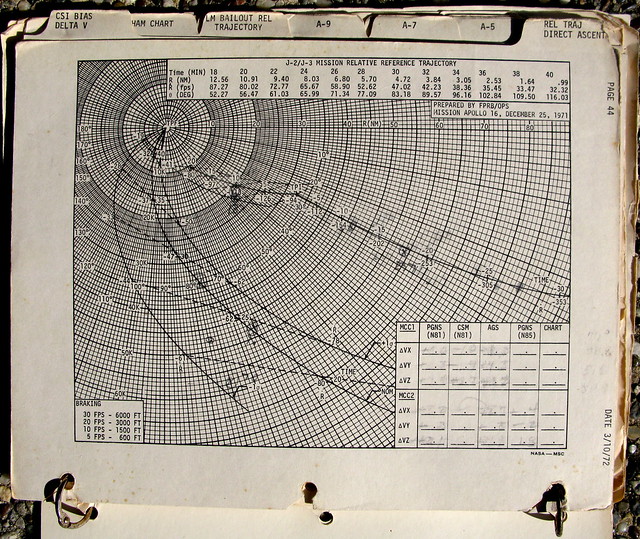

The star charts of Apollo

For millennia, humans have used stars to navigate. For me, one of the most romantic parts of the Apollo missions was that stellar navigation played a fundamental role during the first moon landing. By mirroring the layout of stars and constellations in the night sky in a star chart, it was possible for astronauts to work out the correct course for a spacecraft during a space mission. These were the Star Charts of Apollo.

Designing a usable star chart proved crucial for the success of all Apollo missions, not just Apollo 11. It’s also important to highlight how, like with any successful visualisation, the charts went through various iterations. In each mission, the teams focussed on simplifying the charts to highlight only the constellations they needed. On Apollo they even served multiple purposes: there’s one on-board star chart printed on black paper. Why? The star charts had to double as a sunshade in the lunar module windows!

Technology: converting what’s scarce into abundance — Peter Diamandis

The fourth astronaut

The Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), helped the Apollo 11 astronauts and those who followed safely navigate to the moon and back. At the time, the machine was so advanced that, upon reflection, the engineers who built it said they wouldn’t have undertaken the project if they’d known what was in store. Overcoming these challenges had a significant impact on the wider development of the field of software engineering as we know it today. Due to the complexity of the computer, coders for the first moon landing had to be hugely innovative to pack all the instructions into a machine with a tiny memory capacity. The code also had to work seamlessly: bugs would very possibly lead to the death of the astronauts on board.

Unsung heroes

NASA estimates it took a team of 400,000 scientists, engineers and technicians to put man on the moon. Among these unsung heroes, a couple really stand out. Margaret Hamilton was the first coder hired by NASA and it’s by no means an exaggeration to say her work laid the foundations of software engineering. During her tenure as Director of the Software Engineering Division of the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, she developed the on-board flight software used for the Apollo space programme.

There’s also Elaine Denniston, who worked at the MIT Instrumentation Lab to keypunch data that programmers wrote for the Apollo Project. On the face of it Elaine’s role was a functional one, but her ability to spot and fix mistakes in the code programmers sent her played a vital role in debugging software used during the mission.

How code has changed since Apollo 11

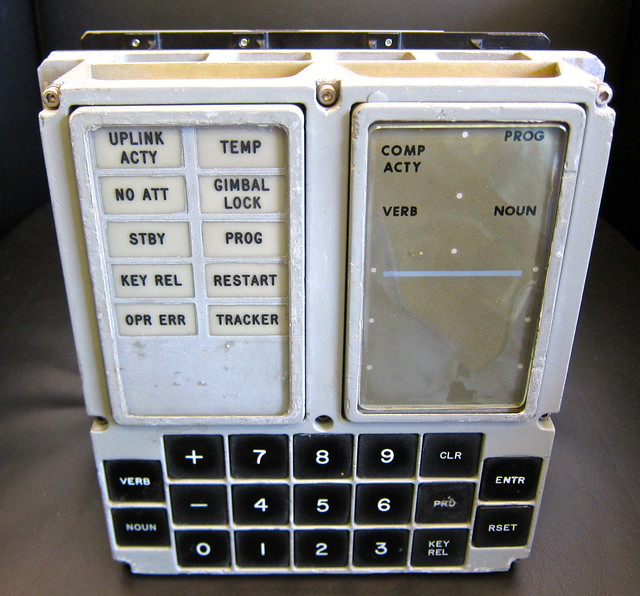

Thinking about equipment required in space, how do you design a user interface to be used under pressure by astronauts wearing bulky gloves? The answer is a user interface challenge that is just as relevant today: how do you balance what users want with the practicalities and restrictions available? Is there room for innovation?

Ramon Alonso, one of the ACG hardware developers, came up with an innovative “verb/noun” interface. Any command could be run by inputting a process name (noun) and a run type (verb). It was revolutionary in its simplicity, but his approach got criticised because it “wasn’t scientific or military enough.” Initially, people wanted what they were familiar with: dials and knobs. This is an early example of the eternal tensions of user interface design: balancing people’s familiarity with the constraints and opportunities provided by new types of display.

“Tindallgrams”

Another hero in the Apollo mission was Howard Tindall, Chief of Apollo Data Priority Coordination. His role was to liaise between engineers and stakeholders and communicate the challenges and compromises. Often known for his humorous “Tindallgrams”, the straightforwardness of his language in memos (here he describes Apollo software as “a bucket of worms”) and meetings helped accelerate Apollo mission planning and execution. These memos reflect the difficulty of balancing money, time and effort that any software project goes through. For most of us, the consequences of failure are small: for Tindall and his engineers, it would likely be fatal.

Ahead of the anniversary of the first moon landing, earlier this year US Vice President Mike Pence made a speech to the National Space Council, during which he revealed the administration’s plan to land humans on the moon again in only five years. He also alluded to a new space race between the US, China and Russia. As we witness refreshed attention toward the space industry, it is important to reflect on the aforementioned technologies and individuals — learning from and championing their achievements. This way, we can ensure those working on current projects are fully informed and a new influx of data and software talent is encouraged into the sector.

Andy Cotgreave is a Technical Evangelism Director at Tableau.