On Thursday 13 September, at around 07:45 eastern standard time, a bomb ripped through the ground floor of a US bank. Medical services were put on full alert, and paramedics were quickly on the scene, attending to the injured on the street outside and reassuring distressed relatives.

Fortunately, the explosion wasn’t too bad. There were no panicking crowds, no falling debris, no eye-stinging chemicals or smoke, no screams or sirens: just casualties that needed resuscitation, reassurance and treatment.

Even more fortunately, this was not a real bomb explosion at all; it was a simulation, a detonation in a virtual world. The injured avatars, and the virtual medics, however, were “real” in the sense that they were mostly employees of Forterra Systems, a provider of virtual world platform software. From their PCs, they performed the medical procedures and acted the role of the injured.

Many now see virtual worlds as a new

way of interfacing with the Internet.

A few minutes earlier, the same audience at the Serious Virtual Worlds conference in Coventry had been given another virtual presentation. Babbage Linden, an avatar representing Jim Purbrick, a senior software engineer at Linden Labs, the company behind the popular Second Life virtual world, spoke about the business applications of virtual worlds. Against a blue sky, with trees waving in a gentle wind, he stood beside a giant, wooden PowerPoint screen, gesticulating with his sparkling, bionic arm.

Weird? Maybe. But not unique: At IBM’s 2007 Lotusphere conference, one presenter gave his presentation simultaneously in the real world, and in two other worlds, Second Life and ActiveWorlds, where an avatar audience watched, mingled and chatted.

Other businesses are doing it too: avatars from Intel, Cisco, IBM, Stanford University and drinks company Diageo all hold regular internal and occasionally external meetings in virtual worlds. Vodafone, the UK telecoms giant, will soon enable text messages sent between avatars to be re-routed to a real mobile.

Meanwhile, military, emergency services and civil authorities are increasingly using virtual worlds for effective simulation, enabling training or for teams to familiarise themselves with procedures and their terrain – worlds which are made more believable because of the presence of other independent people.

The promise

Of course, virtual worlds are not new – computer gamers will argue they go back nearly two decades. But such environments have burst onto the corporate radar over the past two years as the populations have grown, as reports of millions of dollars changing hands filter back, and as some heavyweight corporates announce they have opened shops and islands in public virtual worlds such as Second Life.

Many now see virtual worlds as a new way of working and interfacing with the Internet. John Burwell, vice president of business development for Forterra, likens the mood to 1991, the very early days of the commercial Internet. “The same thing will happen to the virtual worlds that happened with the Internet. It will move out of defence and entertainment into other industries,” he argues.

Certainly, the vision is taking shape. “It’s the next evolution of the Internet – the 3D web,” says David Wortley, director of the Serious Games Institute in Coventry, which has been set up to exploit and promote what it believes will be an explosion in serious applications.

Wortley’s advice to CIOs: “There’s a revolution on the way. You have to be prepared. You should be looking to develop virtual [world] services.”

“It is like going from radio to TV. We found Second Life in 2003 and thought, ‘This is what the Internet was going to be 15 years ago’,” says Justin Bovington, CEO of Rivers Run Red, a branding agency that has re-invented itself as an “immersive spaces company”, helping partners such as Vodafone, Philips, ING Bank and Diageo build a virtual presence

IBM staff are among the most excited about such developments. Roo Reynolds, a ‘metaverse’ evangelist with IBM, says “This is the next iteration of the web. We’ve been through the excitement of the Web 2.0. Virtual worlds add another dimension, a sense of presence.”

Worlds upon worlds

Much of the fascination has so far centred on Second Life (see box below, ‘Trouble in Second Life’), but there are many worlds. Several of the most popular ones are simply multiplayer games environments, such as World of Warcraft, with its fifteen million paying subscribers (Second Life has just 90,000 who pay). In Asia, CyWorld has over 20 million members, mostly in South Korea. Club Penguin, a pre-teen game and world, is believed to have 6 million members.

Overall, there are probably more than 50 such virtual worlds, with dozens serving China, Korea and Japan, where they are particularly popular.

Like the early Internet, interest is matched by a hunger for better technology.

Echoing that, Diageo is to build virtual spaces where employees can hold meetings. It wants to augment those with voice-over-IP links for communications and the ability to exchange documents.

“With video conferencing and many other tools, you have to formally arrange the meeting in advance. I see this technology as replacing that and becoming the virtual water cooler,” says Prentice.

Roo Reynolds of IBM says that that virtual conferences can also be more informal than, say, videoconferencing. Attendees can chat “even when the presentation is on the fly. Virtual worlds are already compelling, even today,” he argues.

This is online conferencing with a touchy-feely sense. “You can go to an event without having to travel, and you still get the benefit of meeting people,” says Jim Purbrick of Linden Labs. At conferences, for example, members can chat to nearby avatars before, during and after presentations.

There are, however, still some problems with Second Life as a collaboration environment. For example, PowerPoint doesn’t work directly – slides must be uploaded as jpeg image files. But these issues are likely to be fixed. Croquet, an open source web project, is planning to provide editable Office files inside its virtual world.

Private islands

One problem with the virtual water cooler is that you can’t always trust public worlds. “You don’t know who is listening and you don’t necessarily know who people really are,” says Prentice of Gartner. And, he adds, it is not always appropriate to do business in places where “the furries are walkng around”.

The answer may be to build a private space. In this way, security can be guaranteed, performance and stability issues can be addressed, and worlds can be built for company-specific applications, such as staff training and simulation.

Another important advantage is that simpler interfaces can be pre-specified by the IT department, and staff trained to use the environment effectively.

IBM’s CIO Office is a case in point. It is building a private, secure world where employees can interact more freely, where they can discuss confidential matters, and which is more resilient than public worlds. Already, it has about 5,000 people who are involved in its “virtual universe” community.

But it is not just the world’s leading companies who are getting involved.

Helped by Ambient Technology, which builds private worlds based on Forterra’s software, the Serious Games Institute in Coventry is planning to build a digital model of the West Midlands region, so that emergency services can train and learn the routes. In Maryland, US, police use Forterra to model roads for clearing traffic accidents.

Forterra says it has projects underway with pharmaceutical and finance companies, and has built worlds for the US military – but none of it is in the public domain. (The US military reportedly has a virtual square mile of Baghdad it uses for training purposes.)

The real thing

This representation of the real environments is becoming important for both private and public worlds. Google, Microsoft, and many others are more interested in building digital representations of the real world, which can then be used for a huge range of applications, ranging from navigation, simulation, security, visualisation; they are also interested in ‘interleaved’ applications, where the user moves between the real world and digital world.

In all of these worlds, individuals can easily join, and their avatars can move around, meet other members, chat (though voice or text), and experience the world in a realistic way. In the games, complex alliances are common, requiring leaders and hierarchies. Most worlds have currencies, and a way of building success and status.

But business has struggled to find a successful role in these public virtual worlds, with branding efforts having little impact, and any revenues earned far outweighed by the investment and effort. Like the early Internet, the level of interest is matched by both the search for the killer application and a hunger for better technology.

Killer app

Is that killer app going to be collaboration? Steve Prentice of Gartner certainly thinks so. He first became interested in virtual worlds when he watched how World of Warcraft players collaborated to achieve their goals. “I realised that the level of collaboration was way beyond the way we use our stilted technologies [in business]”.

Even the sceptics agree that virtual world technology is going to play a big role in business.

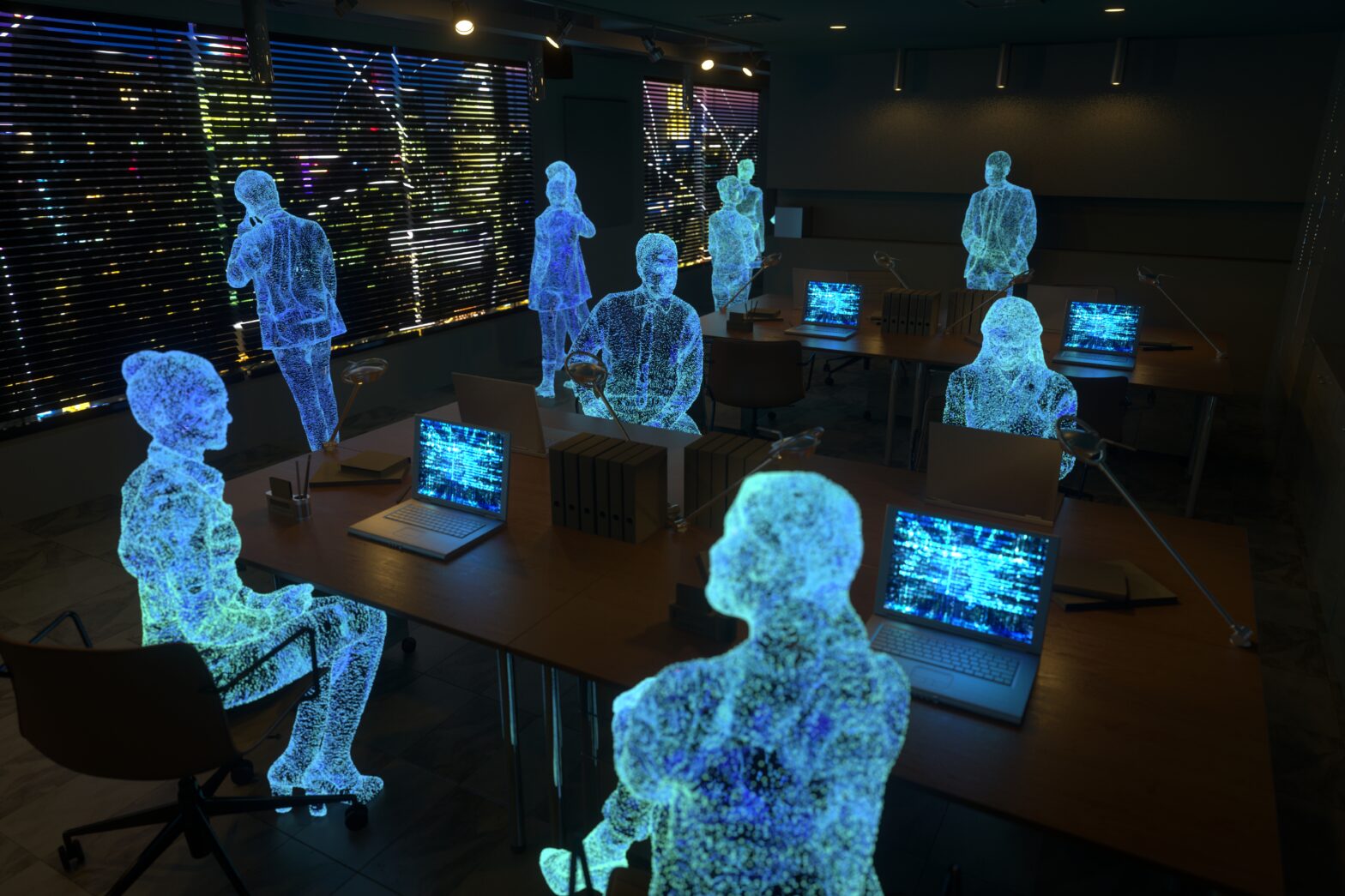

Many seem to agree. Linden Labs uses Second Life for all its meetings, PR agency Text 100 lists Second Life as one of its offices, and IBM and Intel are among those who use it regularly for collaboration. Our main illustration shows a ‘town hall’ meeting of 200 IBMers held in a recreation of Beijing’s Forbidden City, where the avatars of the company’s chief scientist Irving Wladawsky-Berger and CEO Sam Palmisano announced a $100 million investment programme in innovative technologies, including the business use of virtual worlds.

In order to do this, these companies (and others such as Forterra) are developing ways of importing 3D ‘geoweb’ data from GoogleEarth, Microsoft’s Virtual Earth or from other underlying sources, such as ordnance survey maps. These worlds can then be opened up to avatars, and even linked directly to the real world.

But the biggest breakthrough would be if avatars and property could be moved around between the worlds. In October, a number of companies were meeting to discuss just this – with Linden Labs, Forterra, IBM, Cisco all joining in. The goal is, as one insider put, to avoid wasting 15 years in standards battles.

Interoperability isn’t just about the look and feel of objects. Increasingly, objects in different virtual worlds can have intelligence and advanced properties built in, such as weight, flexibility or reflectivity – like objects in advanced computer aided design (CAD) drawings.

One project, at de Montfort University, is even attempting to build large numbers of bots that behave individually, like software agents, so that crowds can be simulated more effectively.

Where is all this going? Steve Prentice, who follows virtual worlds for Gartner, believes that there will be “massive uptake of virtual world technology”. But there is a caveat. He thinks that the “deep immersion” that worlds such as Second Life require will not attract large numbers of people, especially in business. Instead, the technology will be deployed to enhance current working practices where it makes a difference, and where it is easy enough to use.

“I’m very optimistic about the technology. We’ve all gone from basic email to virtual and video conferences. It will lead to a massive [change].”

David Gelardi, vice president of Deep Computing Capacity for IBM, recently told a specialist virtual world web site, 3pointD: “We see this technology moving into banking and retail, and anything where the consumer is involved in a transaction of commerce that they would today do over the web, online shopping, online banking.”

Although many think the 2D is quite sufficient for most online purposes, even the sceptics agree that virtual world technology is going to play a big role in business in future.

And though cautious on many fronts, Gartner stands by a bold prediction: By 2012, 80% of active Internet users will have some kind of presence in a virtual world.

Technology at its limits

VIRTUAL worlds are not only heavily graphics intensive, but to be convincing and truly useful, they must be able to respond to actions of large numbers of individuals, to realistically render events such as trees blowing in the wind, heavy traffic in a city, and, critically, to accurately show human bodily movements and expressions.

That creates all kinds of technical challenges. Second Life, which uses over 2,000 Intel and AMD servers running Linux, has suffered frequent blackouts, crashes and slowdowns, and until a recent fix, regularly had to take its world offline while it upgraded software. To protect performance, limits are imposed on the numbers of visitors in any area at a time.

On the client end, a 33 megabyte download is necessary – and even then, a good graphics card is advisable. Many virtual world critics say responsiveness and interfaces need improving if business is to get more involved.

“IT people in business are a bit wary,” says Wortley of the Serious Games Institute. “But I don’t think we are too far away [from the point] where you have a 3D virtualisation engine in the hardware or the operating system.”

Certainly, the software is getting better. UK games developer TruSim, the “serious” arm of Blitz Entertainment, has demonstrated an avatar that can change its appearance according to underlying medical events, such as rapidly rising blood pressure, heart rate, blood loss, sweat and emotional distress. It recently showed a distressingly realistic demonstration of a man dying in the street. For training purposes, says TruSim strategy and business development director, Mary Matthews, “if you just have something that looks real, but doesn’t behave realistically, the training won’t be as effective.”

IBM, a passionate believer in virtual worlds, is attempting to solve the server-side problems with the first large scale computer specifically designed to support such environments. The system is being built using both traditional mainframe technology and IBM’s superfast graphics Cell processors, which are also used in PlayStations. The platform will use virtual world software from the Brazilian company Hoplon.

IBM describes the computer as “a hybrid that is blazingly fast and powerful, with security features designed to handle a new generation of virtual-world applications, such as the 3D Internet.”

Trouble in Second Life

MOST of the attention around virtual worlds has centred on Second Life, brainchild of Philip Rosedale and his 7-year-old company Linden Labs. Second Life has a rich and powerful visual interface, and a booming internal economy – more than $1 million is spent on most days.

In Second Life there are few rules and no overall objectives, but inhabitants can keep their intellectual property and they can buy and sell goods and services – real or in-world items. “The bi-directional economy is pretty much unique to Second Life and Entopia [a less well known world],” says Steve Prentice an analyst at Gartner.

The economics of Second Life have fascinated many – the world has to deal with issues such as property inflation, currency devaluation and large scale fraud. There is even talk of employing an economic supremo, like the chairman of the Federal Reserve.

In 2006, many high-profile businesses established a presence in Second Life, but since then almost as many have quietly exited. “Second Life is not for everybody. It’s very much an economy driven by individuals who sell small value items and lots of them,” says David Wortley. “It’s an environment that allows people to experiment. It’s not a serious and stable ecommerce system.”

Gartner gives similar advice: “If you are considering virtual worlds for online marketing, then you should think again. Organisations tend to veer towards Second Life, but they should step back and assess it like any other channel.” Second Lifers are actually mostly over 30, he points out, but they are “anti-enterprise…they are the type of people who are fiercely creative and protective of their own enterprise.”

Clive Holtham, Professor of Information Management at Cass Business School, takes a much more critical view of the whole virtual worlds phenomenon, citing performance problems, stagnating membership, limits on meeting size and poor collaboration tools. “If I was a 3D multimedia artist who likes to create unbelievably complicated models, I’d say it’s brilliant. But I’d recommend that most business and universities ignore it and focus on other technologies. I’m not sure Second Life can escape its own history.”

Even the first wave of converts is getting concerned.

“I sell virtual world platforms, but I don’t hang out in them,” says Ron Edwards, a former head of e-learning at Unilever and now CEO of Ambient Performance, a small UK company that helps businesses build private virtual worlds. “There’s a huge difference between giving people the keys to Second Life and saying ‘go play’, and setting a world up with a serious purpose.”

Justin Bovington of Rivers Run Red also agrees that the initial model of “roll up, create an island and see what happens” doesn’t work. Now the focus has shifted to how businesses can use virtual worlds to be creative, interactive, sustainable and efficient. “We’re moving very quickly into the second wave”.

Glenn Fisher, director of marketing and programming at Linden Labs, says none of this is surprising. “We started out as a consumer company. In 2006, we saw a lot of people try to make or sell to the consumer, and for the most part that hasn’t worked. Why buy clothes or books when you can do that on the web or in stores?”

However, he says that in the past year, there has been a strategic shift: “Now they are looking at how to use it for their processes.” He cites the University of Illinois, which has built replicas of local city blocks, which are used by the fire and health departments for training; and many others building areas for collaboration and engaging with customers.

And that points to a very different future for virtual worlds.